Here’s a big question for you – why do we like rock music?

Is it the visceral thrill of the guitar? The pounding of the rhythms? That classic rock n’ roll attitude?

No, it’s because it reminds us of animals in distress of course… wait, what?

The Daily Mail has reported on a university study that suggests the psychological reason we like rock music is because the distorted sounds and jarring tones are closely reminiscent of animal distress calls, therefore bringing out our own primal, animalistic tendencies.

The study comes from a team from the University of California, who have published their report in the peer-reviewed scientific journal, Biology Letters, and could well be the first of its kind to incorporate scientific studies of animal communication with music perception.

One of the study’s authors, Daniel Blumstein, is an authority on animal distress calls, and says that “music that shares aural characteristics with the vocalizations of distressed animals captures human attention and is uniquely arousing.”

As the chairman of the UCLA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Blumstein originally led a team of researchers in 2010 to study the soundtracks of over 100 films from various genres, from the classics to adventure, as well as war and horror movies – to discover patterns or characteristics in their use of sound to illicit emotional responses.

Their research determined that the scores of particular genres each contained specific tricks and unique characteristic to manipulate emotions. The frequencies of a dramatic movie, for instance, would abruptly shift up and down while a horror film would use more distorted sounds at regular frequencies.

Nothing particularly new there, but Blumstein noted that researchers were also able to isolate recordings of animal screams and distress calls in some film soundtracks.

All well and good but what does that have to do with rock music you ask?

Blumstein then took the findings from his film research to Greg Bryant, a fellow academic in the field of vocal communication and evolutionary psychology; who also happens to be a musician and recording engineer. Together the pair composed short ten second synthesiser-based pieces that mimicked the emotional responses of their film studies.

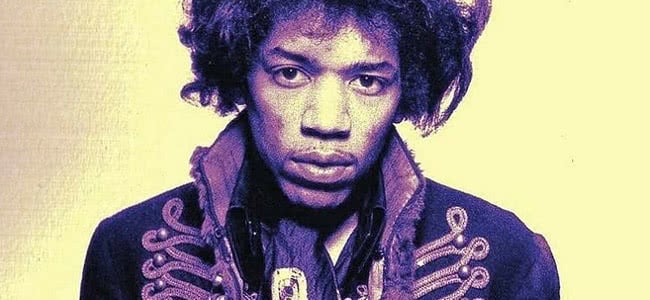

Blumstein and Bryant then used their original music to test types of emotional conditions. One type of condition was considered to be controlled, music that was generic and emotionally neutral, without noise or abrupt distortions; which Byrant likened to elevator music. While the other condition, Bryant likened to Hendrix’s distorted outbreak at Woodstock, music that began placid but suddenly broke into distorted or jarring effects.

The aim, says Blumstein, was “‘we wanted to see if we could enhance or suppress the listener’s feelings based on what’s going on with the music.”

The two kinds of music were then played for a number of students, who were asked to rate their response to the compositions based on how whether it provoked a positive or negative feeling, and how arousing they found the music. Blumstein and Bryant’s team found that the music that broke into distortion was rated as more exciting that those that did not, yet more likely to be described as provoking negative feelings.

Blumstein likened the results to those he’d found in the animal kingdom, particularly his own studies into marmots. The researchers decided that there was a correlation between the intuitive composition of music and its emotional response.

“What [composers] usually don’t realise,” says Bryant, “is that they’re exploiting our evolved predispositions to get excited and have negative emotions when hearing certain sounds.”

“This study helps explain why the distortion of rock ‘n’ roll gets people excited: It brings out the animal in us,” Bryant says.