So the story goes that when the Beach Boys were recording ‘Caroline No’, Brian Wilson wanted the ending to be melancholic with the sounds of a train and dogs, instead of instruments.

The strains of the choo-choo came from a 1963 sound effects album. The canine yap-yaps were from Wilson’s pet collection, a beagle sadly lumbered with the name Banana and a Weimaraner which answered to Louie, who was used in place of instruments.

If that wasn’t strange enough, Wilson turned to the studio engineer and asked, “Is it possible we could bring a horse in here if we don’t screw up?” The horse never made its recording debut.

But the tale does show that rock musicians have been working at trying to get a “different” sound for close to 60 years, even to the point of making their own instruments.

An early example was Queen guitarist Brian May. Now close to being a billionaire, May grew up in a poor household but had an electrical engineer father Harold who had enough smarts to build the family’s TV and radio sets.

Over two years, father and son built Brian’s signature guitar The Fireplace out of, well, yes, the family 100-year old fireplace, (complete with worm holes which he filled in with matchsticks) a bit of a table, a motorcycle spring and mum’s knitting needle as pat of the tremolo.

May had seen Jeff Beck onstage coaxing wonderfully weird sounds by holding his axe up against his amps.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

He recalled, “I think I was the first person ever to make en electric guitar that was designed to make feedback to make it swing, rather than see it as a nuisance.”

Two Australian examples would be J. Walker aka Machine Translations using unconventional effects like broken pianos with the front removed and strings played directly, and Kimbra’s experimental onstage set-up, which she explains below.

Bjork – The Ganeleste

For her ambitious multimedia Biophilia project, the Icelandic envelope-pusher wanted a hybrid of the celeste, a spectral piano featuring small steel bars and used on 2001’s Vespertine, with the Balinese/ Javanese gamelan.

These are a range of percussive instruments, including metallophones played by mallets, hand-played drums (kendhang) and banana shaped idiophone (the kemanak).

British percussionist Matt Nolan and Icelandic organ craftsman Björgvin Tómasson spent ten hectic nail-biting days to build it. It was used with great spectacular effect on the track ‘Crystalline’.

The Biophilia tour also took along two massive pipe organs, which by using the celluloid motors under each key, allowed them to be controlled by remote.

Check out ‘Crystalline’ by Bjork:

Bjork – Gravity Harps

Another Bjork idea to provide spectacular sounds that also opened up more creative opportunities were Gravity Harps, for which she already had the track ‘Solstice’ in mind.

These were 10-foot tall acoustic, robotic pendulum string instruments.

The design took Andy Cavatorta and his team – which included mechanical engineers, sculptors and robotists – seven months while their production ran late by six months.

Cavatorta explained the set-up to Vice: “There are four pendulums, each with a cylindrical harp on the end.

“As each pendulum swings through its lowest point, a single string on its harp gets plucked. The harp is cylindrical and can rotate, so any one of its eleven strings can be played by facing it to the plucker.

“There is also an ‘empty’ string position for playing rests. The four pendulums all have the same periods. But their phases are offset so they play in order 1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4.

“They could also play other rhythms. But this metronomic setup works really well for the song ‘Solstice’.”

Boredoms – Seven neck guitar

Japanese avant-garde noiseniks Boredoms have a thing abut the number 7. In their dialect, it means “plenty” and fits in with their mission “to share”.

They once staged a performance on July 7, 2007 in Brooklyn, New York, where 77 drummers were roped in for a 77-minute long piece named ‘77 Boadrum’.

So a seven neck guitar was an inevitability. Of course the guitarist doesn’t put the monster on and risk breaking his neck.

The seven necks are set to different tunings and placed on a rack on top of an amplifier, and “attacked” with a drumstick.

Check out their seven-neck wonder:

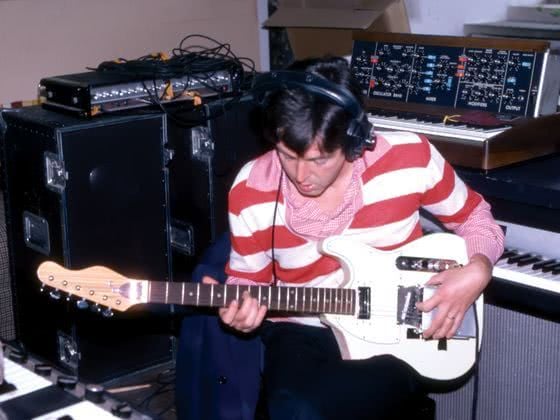

10cc – The Gizmotron

In the mid-’70s, British art-pop band 10cc (‘I’m Not In Love’, ‘Dreadlock Holiday’) couldn’t afford to record with an orchestra.

So two members, Lol Creme and Kevin Godley, came up with The Gizmotron or The Gizmo, as a guitar and bass guitar which could make violin squeaks.

This was in 1975, and the polyphonic synthesiser and digital samplers were still some light years away.

We are told, “Taped or permanently attached to the body of an instrument, the Gizmotron uses small, motor driven plastic/rubber wheels to make the strings vibrate, yielding resonant, synthesiser-like sounds from each string.”

It was used on records by Paul McCartney’s Wings and Led Zeppelin.

It soon swelled to making a multitude of sounds – so much so that when Crème and Godley left 10cc to concentrate on the contraption, a 1977 album called Consequences (to show off what it could do), needed six sides to do the job.

In 1979, a company Musitronics was licensed to make it for public consumption.

But the commercial version was of uneven quality and unreliable, and the company went belly-up in 1981. It made a return under another company a few years ago.

Kraftwerk – Laser Drum Cage

In their recording studio in Germany, Kling Klang, Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider happily whipped up a witches’ brew of strange looking things like vocoders and drum kits.

Their best known is the laser drum cage, in 1976. The idea was that Wolfgang Flür would stand in it and, moving his arms through beams, activate percussion sounds.

It was unwieldy, unreliable and a nightmare, and our heroes lost patience with it and started to use an electronic drum kit.

Iannis Xenakis – Sixxen

When the late Paris-based Greek composer Iannis Xenakis created his 1979 percussive work Les Pléiades for a marimba-looking 19-note instrument he called sixxen after six and Xenakis.

The six was for the six percussionists required who perform the piece, each to have “19 metal sounds each, which should be neither chromatic nor diatonic tuned” and create a drone-like effect.

The piece was performed in Australia in 2011 by local percussion group Synergy, using Xenakis’s designs and scouring scrapyards for months to get the metal that could get the sounds that he dreamed up.

Check out ‘Pleiades’ by Xenakis:

Sleeping Dogs Lie – Gallon bucker drum kit

When it came to making his sixth album Trieste (2009) Sleeping Dogs Lie aka New Mexico alt-rock singer songwriter Eric Guenette decided he was over the idea of drum machines.

So he went back to basics, and built a drum kit out of five-gallon buckets, “garbage bags and a shower curtain as heads”, a golf ball for the kick mallet and an old silver tray for the cymbal.

But… and you knew there’d be a but – when he started recording with real instruments with this new contrivance, it didn’t sound right.

So the solution was to build a whole array of instruments himself. This included a guitar using twine, fishing line, and wire for strings, and bolts for tuners.

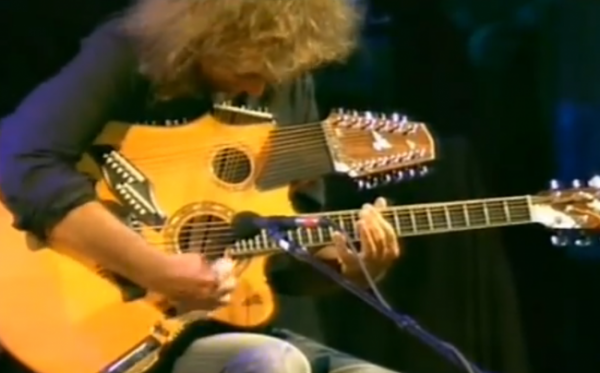

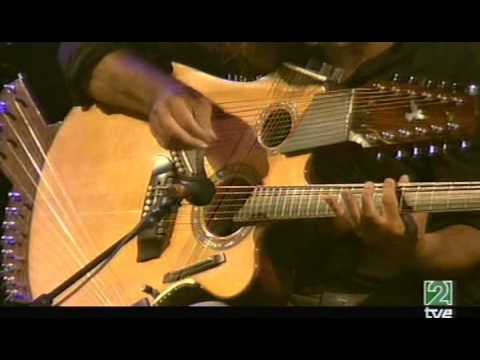

Pat Metheny – The 42-string Pikasso guitar

After playing with harp guitars In the early ‘70s, the US jazz guitar virtuoso had the idea of four-necked, 42-stringed around then.

The first guitar maker he entrusted with the job took the money and disappeared.

Then he found Canadian luthier Linda Manzer who spent two years on developing his idea, including the hexaphonic pickup, which allowed him to trigger off samples.

The final result looked like a cubist Picasso painting, hence the name. It took Metheny a few years to come to grips with it, “I couldn’t really figure out how to tune it.”

Check out Pat Metheny’s 42-string guitar:

He later invented the Orchestrion – which served as his entire backing band.

“I didn’t know quite what to expect when I started this whole thing, especially when I was making a record with it.

“The result was nothing like I would have imagined.”

Pat Metheny explains and demonstrates the Orchestrion

Vegetable Orchestra

Before a performance, Vienna’s Vegetable Orchestra go to the local market and buy the vegetables that will serve as their instruments in a few hours.

Some, like peppers are already ready to play.

Others, like carrots, pumpkins and courgettes have to be carved and turned into, respectively, recorders, bass drums and trumpets.

They refer to this two-or-three-hour process as their soundcheck. Whatever vegetable pieces are left over, are put into a soup, and served to the audience after.

Check out the preparation and performance by Vienna’s Vegetable Orchestra:

James Morrison

Of course Australian musician James Morrison didn’t invent the trumpet. They came into being in 1500 BC and were used when our ancestors were out in battle or going on a hunt.

Being a bit of a perfectionist, Morrison explains, “I like the trumpet to be warm in sound, when I play gently, and to get brighter when I play with a lot of air.

“Any trumpet will do that but I like it to be accentuated and with a combination of the metals used you can make it happen.”

Morrison was drawn to Austria’s Schagerl company for their “dark, Germanic-Viennese sound” and together they created the commercially successful JM1, JM2 and JMX models.

There’d be a yellow brass ball for quicker response or gold brass bell for greater warmth.