Music documentaries often fall into a familiar trap. They present an unceasing parade of talking heads, all attesting to the mastery and ingenuity of the band the documentary is about, sometimes to the point where you wish to revoke the reputation of said band.

This is problematic enough with a traditional rock outfit but when you’re focusing on the greatest avant-garde rock band of all time, The Velvet Underground, more has to be expected; director Todd Haynes’ new film on the seminal New York band understands this and I’m thankful that he did.

His documentary is artful and unconventional, disturbing and alienating, four words that could also describe The Velvet Underground themselves. It’s Documentary As Performance, unsurprising from the director who made a Bob Dylan biopic featuring six different actors (including, most stunningly, Cate Blanchett) portraying the icon.

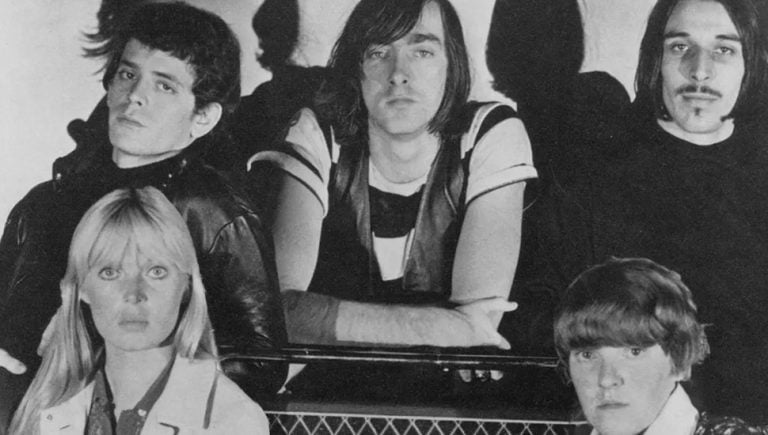

The Velvet Underground were famously associated with Andy Warhol and The Factory and Haynes makes wonderful use of Warholian split screens throughout, longform shots of the band members staring simply but intensely into the camera. There’s Lou Reed, eyes screaming hatred for something, for anything, with the glint of genius lurking too; there’s the cool detachment of John Cale, the look of a man who knows his superior musical talent.

It’s an electric symbiosis, audience and artist connected by Haynes in a completely unexpected way; as Reed and Cale narrate their own lives in the background of the split screen, it’s as if they’re listening to it for the first time with us.

The artistic direction of Haynes’ film was predetermined by the sad fact that very little concert footage of The Velvet Underground is available. Instead, he weaves archival footage, often captured by Warhol himself, still photos from 60’s New York, and talking together in an avante-garde composition.

Maureen “Moe” Tucker, their effervescent and charismatic drummer, is interviewed at length, as is John Cale, the only two remaining members from the original lineup. Cale discusses cooly and calmly his contentious relationship with Reed and authoritatively talks about music but it’s Tucker that really captivates: this little woman, competing with the egos of Cale and Reed, the famed beauty of Nico, the laidback talent of Sterling Morrison on guitar, was always there during the madness and the ecstasy; as she recalls those times, now aged 77, she remains remarkably humble about it all.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

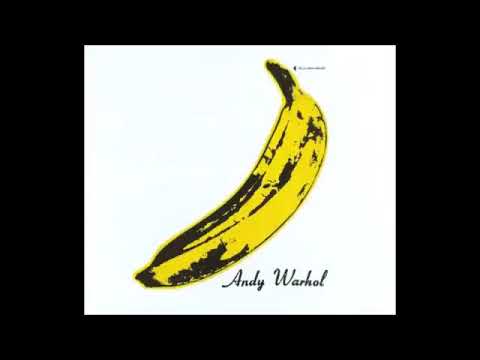

Brian Eno famously said, “The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band,” and it’s Jonathan Richman who best exemplifies this in the documentary: the proto rock legend talks with a feverish intensity and an unyielding passion for the effect the band had on his life, from being given their first album by a friend as if by fate, to describing the unique playing style of each member, to remembering the magic of seeing them in concert.

The documentary is also a poetic snapshot of New York City in the 60’s. All the seductive intensity of Warhol’s Factory scene – The Velvet Underground were his house band for a time – flashes across the screen, legendary artists appearing – poet Allen Ginsberg, filmmaker Jonas Mekas, Warhol icon Mary Woronov, writer Amy Taubin, musician La Monte Young – and disappearing just as quickly. Their lives somehow feel both very present and very distant.

No one should expect a standard account of the band’s progress: although it’s mostly chronological, Haynes is enamoured with the classic lineup of Reed, Cale, Morrison, and Tucker. Once Cale departed after one too many disagreements with Reed, replaced by Doug Yule, Haynes didn’t so much lose interest in the story as realise his point had already been made.

Haynes, you feel, believes in the Art of The Velvet Underground, the transgressive outsiders, the avant-garde provocateurs, the foursome who wore all black even when they arrived in a searingly hot California on tour.

The film ends with a melancholic montage running through what happened to the band’s lives and careers after the end of The Velvet Underground.

They released their own records, all of differing styles, but nothing came close to what they achieved together. We’re reminded that the magnetic and enchanting Nico is now gone, having died in a cycling accident far too soon in 1988; we’re reminded that Morrison passed away in 1995, aged just 53, long after he’d settled into a quiet post-Underground existence as a, amongst other things, tugboat captain; we’re reminded that Reed, one of the most distinctive presences in music history, died in 2013.

As the film ended, I was left with a daunting emptiness. I don’t think another band as radical as The Velvet Underground will ever come again; I think the conditions of music culture and economics as they are now preclude this from happening. Art can be difficult as well as being essential, though, and Haynes’ film is a timely reminder of this. Maybe, if we’re lucky, 10,000 people will also see his film and be inspired in some mystical way as all the bands that followed The Velvet Underground were once before.

The Velvet Underground is available to stream on Apple TV+ now.