In the wake of recent news that Apple has become the largest corporation ever, one of the most interesting (fake) news stories of the past few weeks is that of Bruce Willis suing them over being unable to bequeath his digital music library to his daughters once he passes away.

It was reported that Willis recently discovered that legally, he does not own the material he has paid for on Apple’s iTunes store in the traditional unspoken contract of a purchase, but instead that the material bought on iTunes is only ‘leased.’

Put simply, when you pay for music on iTunes you are paying for the ‘right to use the music’ on your iPod, iPhone, or other device; and while there’s no reason one couldn’t simply give their children their log in details – or indeed the computer the songs are kicking about in – it begs for a very interesting discussion. What does a future in which people cease to own their music collections look like? And will it be good or bad for music fans?

Physical sales of music are consistently dying as people increasingly purchase their music online and in the digital format. Between 2000 and 2009 physical sales of music dropped by over 70%, and it’s set to drop by that same amount again between now and 2016.

So more and more, people’s musical collections are making the transition from physical to digital. But as it turns out, when we purchase music digitally we’re merely purchasing the right to listen to that music. What this means is that as time goes on, people’s music libraries cease to be a music library they own and can pass on.

Even the idea of cultivating a music library is under threat with the advent of music streaming services such as Spotify, which boast access to 16 million tracks for a low monthly price of absolutely free. You don’t need to be an oracle to see where the future’s heading.

At some point in the not-too-distant future we will find ourselves in a post-ownership musical landscape. And if that’s not scary enough, a whole new generation of children will grow up in a world where nobody actually thinks about owning or collecting music, let alone paying for it.

Reportedly, Bruce’s biggest worry was that he couldn’t pass on his cherished music collection to his children in order to help inform them, and for them to inform themselves, of the rich musical heritage Bruce had spent a lifetime obtaining.

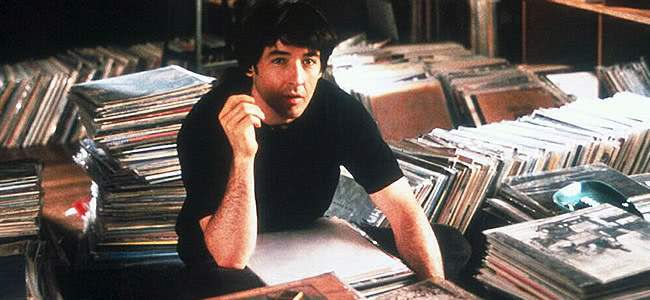

This is no fleeting fancy; almost anyone can pinpoint a moment in which their musical tastes have been informed by their parent’s good (or embarrassingly bad) musical taste. Who hasn’t rifled through their dad’s old stack of vinyl (or cassettes, for that matter), or stolen a cheeky CD or two from their mum? Losing that kind of inter-generational musical tradition could have a myriad of effects and seems pretty daunting.

The danger of only having music libraries that can be accessed (as opposed to possessed), is that when you’re online, you’re constantly doing more than one thing at a time. Whether it be talking with friends, reading news articles, studying; you’re distracted, and music becomes just another open tab.

Grizzly Bear member Chris Taylor recently lamented the digital revolution. In a forthcoming interview with Tone Deaf, he painted a blunt picture of what is happening today: “It’s like, ‘let’s check out the new album, slash look at my Facebook the whole time, and walk away from my computer for a while’.”

If you’re only hearing music while distracted by two or three other things, you’re never fully engaging with that music. The true worry is that as people increasingly access rather than own music, they’re increasingly hearing, rather than listening to music.

What does this mean for the music being created? At its bleakest it means that the music becomes merely a commodity, something simply to be there to avoid silence. It makes music a peripheral accompaniment rather than what music truly is (or aims to be): art.

There needn’t be any deep message behind the lyrics, no great musical intricacy between its performers. It just needs to sound attractive enough to be heard, but not intrusive enough to require the listener to engage with it.

A potential outcome is one which has long been touted as an inevitability of the digital age, the ‘death of the album’.

As younger generations increasingly spend their time meandering through the web, logging into a worldwide music catalogue that is never theirs, there ceases to be a need for music as a tangible, collectable artefact.

As people invest their money towards a monthly fee, which entitles them to merely access a music library (albeit a huge one), there are less people investing in albums, both financially and consciously. At what point does sifting through an album’s liner notes and lyrics or marvelling at the album’s cover truly become a thing of the past?

Hopefully never, and as more people stream music online (or download it – legally or otherwise), there is a growing contingent of music fans who are touting vinyl as the last bastion of music collectability.

As CD sales continue to plummet, sales for vinyl are on the rise, with a 39% increase in 2011, and a further 10% over the first half of 2012. As many see it, vinyl forces the listener to engage with the music more than other mediums. One has to carefully drop the needle, flip the record halfway through to hear the rest; there is an active engagement with the music which the simple click of a mouse does not bring.

Perhaps as more people head to music-streaming, so to will more people demand their physical albums and the niche market of vinyl enthusiasts will grow into a formidable force. But it’s impossible to imagine vinyl ever slowing the tide of online music licensing; after all, it put up little resistance to the CD onslaught of the 80s.

It’s hard to imagine what the future truly holds if, rather than having your own music collection, listeners log in to worldwide music libraries. Whether the story is true or fake, Bruce Willis should have the right to pass his music collection onto his children. And so should you. Imagine if you’re not legally allowed to pass your digital music collection onto your children.

What will the post-ownership musical landscape look like? At the moment it’s hard to say; but a world without record stores & fairs, collectors editions, and even the humble records collection, doesn’t sound too good to us.