Spotify has already drawn considerable attention over its business model recently, and now the popular streaming service has found itself at the centre of a copyright infringement lawsuit.

Ministry Of Sound, one of the world’s largest independent label groups, has filed a legal attack on Spotify in the UK High Court this week that claims the service has allowed users to routinely steal and ‘copy’ its many successful dance compilations, by replicating the tracklistings of its many compilation releases.

The dance music company alleges that Spotify is refusing to delete offending playlists – many using the same Ministry Of Sound names in their titles.

The lawsuit essentially argues that the curation of its successful compilation albums should be considered as intellectual property under copyright law.

“What we do is a lot more than putting playlists together: a lot of research goes into creating our compilation albums, and the intellectual property involved in that. It’s not appropriate for someone to just cut and paste them,” Ministry Of Sound CEO Lohan Presencer tells The Guardian.

The dance music brand is seeking an injunction requiring Spotify to remove the offending playlists and to permanently block similar playlists from appearing, as well as an unspecified amount of damages and costs. Presencer says that the company has been pressuring Spotify to remove playlists since 2012; “It’s been incredibly frustrating: we think it’s been very clear what we’re arguing, but there has been a brick wall from Spotify,” he says.

While Ministry Of Sound has benefited from selling an estimated 50 million copies of its popular dance music compilations in the two decades since it was founded, the new ear of streaming music represents a threat to their traditional business model. The vast majority of tracks that make up all those Annual, Sessions, and Best Of‘s are licensed from other labels.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

“When we license our compilations, which include a lot of major-label repertoire, they do not grant us the rights to stream those compilation albums,” explains Presencer, meaning that Ministry Of Sound misses out on the revenue generated from the offending Spotify playlists that copy their tracklistings.

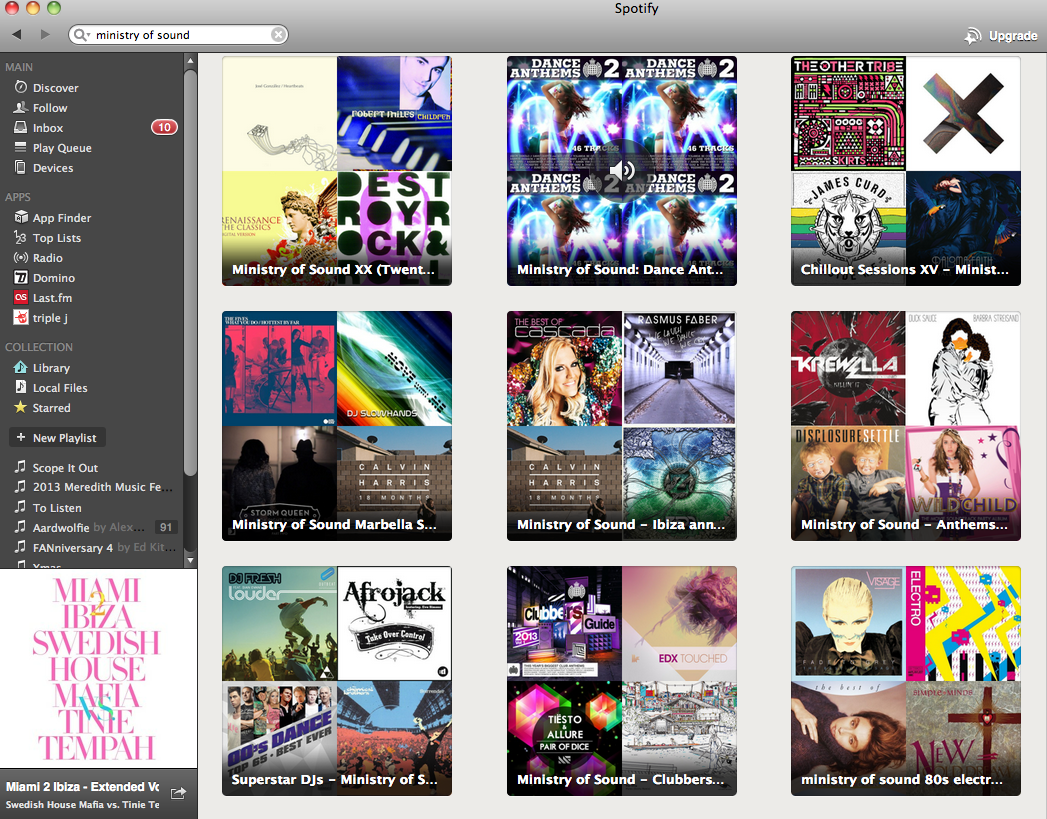

(User-generated Ministry of Sound playlists on Spotify)

While Ministry Of Sound has a separate label division that signs and develops artists and therefore owning the rights to sell and stream their music, thus far, the company has held out on making these tracks available to stream on Spotify as part of its 20 million song library that’s accessed by 24 million users worldwide.

“Spotify only remunerates you for content ownership. It doesn’t pay you if you’re compiling third-party content,” Presencer says. “We’ve been asking them about this for the past four years, and have tried to engage in dialogue with them on how they would remunerate us for curation. They’ve said they don’t have a structure for that in their model.”

Ministry Of Sound’s lawsuit hinges on the idea that compilation albums qualify for copyright protection – as in the selection, placement, and arrangement of their running order, as Spotify clearly has the rights to the individual tracks that a user may add to their own custom playlist (to date there are over one billion playlists created on the service since its 2008 launch), but Ministry of Sound are arguing that curation is a kind of intellectual property, one they want protected.

“Everyone is talking about curation, but curation has been the cornerstone of our business for the last 20 years,” notes Presencer. “If we don’t step up and take some action against a service and users that are dismissing our curation skills as just a list, that opens up the floodgates to anybody who wants to copy what a curator is doing.”

The Guardian reports that a spokesperson from Spotify acknowledged the lawsuit but declined to provide any additional comment.

The streaming service has already come under great scrutiny in recent months from musicians and industry alike. A spotlight arguably made brighter after Thom Yorke and Nigel Godrich of Atoms For Peace/Radiohead fame publicly pulled their music from the music streaming service in protest, proclaiming that Spotify was “bad for new music” with a royalties model that pays artists “fuck all.” An analyst from Australia’s royalty collecting agency APRA|AMCOS agreed, albeit in less colourful language, saying that the pittance in royalties that Spotify and rival services pay emerging artists “needs to be fixed.”