Sticky Fingers are a band straddling two worlds in Australian music – they are despised by the media and adored by the public. While the music media tweets with vitriol and posts one sanctimonious hot take after another, the band drives forward, booking sold out tours and posting happily on their social media accounts to a gaggle of devoted fans. Sticky Fingers are the Donald Trump of Australian Music.

Speaking this week with a powerful booker, they had this to offer on the subject. ‘Honestly I know its a laboured parallel but it reminds me of Trump supporters… this real “us against the world” mentality.’ The sources quoted throughout will remain anonymous because of their position in the industry.

The band is being held accountable for the few things they have done (or haven’t done) as a placeholder for the media’s inability to report on open secrets and hearsay. These secrets are passed around amongst a group of chosen insiders, who grow angrier and more disconnected from the people they are supposed to be reporting to.

The thing about open secrets, however, is that they are still secrets. If something is not reported on, does it really make a sound? What is the reality of who Sticky Fingers are? The Worst Band in Australia? Or the survivors of a Hateful Media Campaign?

Adored by the public, hated by the media

Jeeze that Sticky Fingers comeback is going off without a hitch huh. Just swimmingly. https://t.co/S7B76glF9y

— Josh Butler (@JoshButler) May 18, 2018

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

Before Donald Trump was elected, he was chided and derided by the media. He was called ridiculous, disgusting. His policies were mocked, his appearance caricatured and his lifestyle and character vilified. Upon his election, I was working with a leading journalist from the Sydney Morning Herald. ‘We’ve had to put everything on our project on hold Phoebe,’ he said to me in an email,’ Because of the Trumpocalypse.’

Before the election of Trump, the media spoke of the US election as if it were a sure thing for Hillary Clinton, like Trump as president were, of course, not a possibility. The result was humiliating for the media, highlighting a sparse disconnect between internal media cognizance of political trends and the actual opinions of the people that the media are supposed to be servicing.

Now, I’m not saying President ‘Grab Them By the Pussy’ Trump deserves any sympathy, but I would dare to suggest that the leader of the free world was somewhat of a trailblazer for highlighting the media’s ability to self-perpetuate, to cycle in its own safe echo chamber – to forget about the public. And to ultimately prove to us all that the media is not as powerful as it likes to think it might be. That ultimately, the power lies in the hands of the majority.

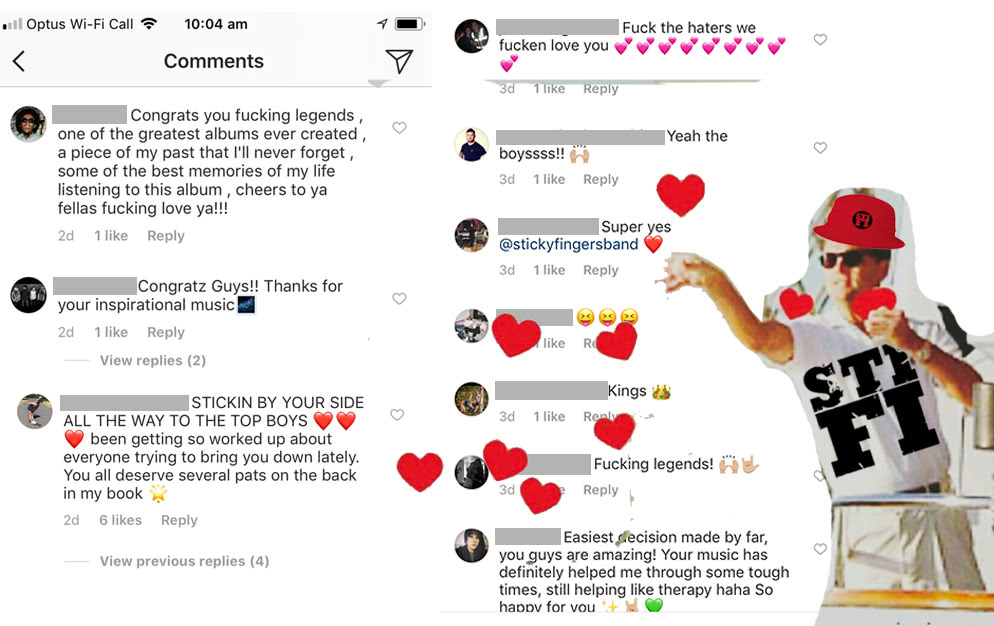

Last week after Frost was thrown out of Kelly’s in Newtown, I looked at my Twitter newsfeed, which is heavily populated by Australian music industry, and I saw the depiction of a devilish band of reprobates and the longing cry that we never hear from them again. As you flick over to the band’s official social platforms, which service their fans, a completely different story is told.

“Fandom’s a wild thing.” Says one source. “If you support a band, you support them through attacks and if you support them through attacks, you’re putting in roots that you’re not gonna walk away from.”

On ‘ruining careers’

dylan frost retire* bitch

*hold yourself accountable for the violence and pain you have caused, both directly and indirectly

— Shaad D’Souza (@shaaddsouza) May 19, 2018

At the start of April, Noisey ran an article calling out Sticky Fingers for their return to the music scene after a one year hiatus. The hiatus was addressed by the band in two separate Facebook posts. The author asserted that the harm enacted on the alleged victims from Frost’s alleged behaviour/s had not been sufficiently addressed by the band, and the alleged victims had not been properly redressed. The victims remain unnamed, unnumbered, mysterious, but are used to make a number of redressements to the band, the music industry and the media at large.

“Taking time for ‘rehabilitation’ without acknowledgement of the harm done doesn’t help the accused or the accusers.” D’Souza wrote, going on to question “the legitimacy of #MeToo and #meNOmore in the [Australian music] industry. Aside from some dissent on social media, Sticky Fingers’ return has, by and large, been accepted without question by the Australian music industry.”

“If ‘zero tolerance’ is the #meNOmore mantra, why hasn’t it applied here?’ D’Souza asked, possibly trying to skewer the band themselves, but seemingly laying blame on the grassroots #meNOmore movement for not doing more. D’Souza outlined overseas examples of the USA and the UK, where ‘accusations against artists like PWR BTTM and Matt Mondanile have been believed with little question… Meanwhile in Australia, such accusations tend to be critiqued, questioned and pulled apart—then forgotten or brushed aside.”

It’s easy to look abroad at the success of the #meToo movement, compare it to Australia, and lay blame on journalists, industry folk and founders of movements like #meNOmore. While the dissonance in reporting might seem like ‘inaction’, I would posit the situation D’Souza speaks of is more of an apples and oranges situation, legally.

In Australia, reporting on #MeToo stories is often a crime

Because Australia is not the USA, and we do not have constitutionally protected rights to Free Speech, reporting on #MeToo stories is kind of, ahem, illegal. Australian defamation laws make it excruciatingly hard for journalists to report on the kind of abuse associated with #MeToo or #meNOmore – reporting single person accounts of abuse, often told before (or never with) any police involvement, is a crime.

“Australia’s restrictive defamation laws work against the whistle-blowers,” writes Steph Harmon for The Guardian, while recapping the Australian #MeToo movement in a larger context. Tracey Spicer’s aggressive campaign to corral the stories of abuse victims and have them reported on, she admitted, had hit roadblocks with larger publishing houses shying away from both the legal implications and for the stories ‘getting a little too close to their executives.’

Defamation and you

But I digress.

The idea behind defamation is that individuals are protected when ‘malicious’ or ‘untrue’ things being published about them. Defamation laws in Australia circulate around the ‘possibility’ that a ‘suggestion of character’ may affect an individual negatively, in any way. This means that, in reality, it is very easy for perpetrators to first of all prove that stories highlighting abuse are harmful to their reputation and career.

The second legal death knell is to allege that the abuse is ‘untrue’ which is very easy if the police were not involved; nobody was witness to the abuse; there was alcohol involved; the victim is of any kind of questionable character; the victim was intoxicated; etc etc etc.

How many hot takes will it take?

I have recently heard no shortage of allegations about the bad boys of the Australian Music Industry, going around and around like whispers inside of a certain clique. Occasionally, a person will lose it and stick their head out over the parapet – usually on Twitter. Make no mistake, industry people talk. But this in and of itself is illegal.

There are things I have been told about a number of Australian artists are things I could never report on, as maddening as that may be. Reporting on #MeToo sorties would result in me immediately being sued, for enormous amounts of money; I would also definitely lose the court case. Whispers, rumours and bitching have become a thematic marker for the Sticky Fingers narrative, engaged in by both the media and the band themselves, who often reposition themselves as the victim.

“Dylan Frost* retire, bitch!” is a tweet I came across this week, from one of the most powerful music editors in the country. I also went to look at Paddy J Cornwall’s Instagram, which featured this quote.

“‘I’m going to ruin your career’ – said a fellow ‘artist’.”

Just like an election, partisan lines are beginning to be drawn.

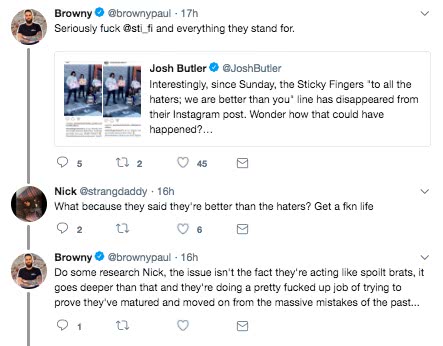

Speaking to an industry insider, they cast a wider critique of the dialogue forming around the two camps. “It’s becoming a little music scene referendum on whether you’re a bleeding heart [social justice warrior] or a true rock fan who knows the boys will be shit sometimes. The band are feeding that [narrative], it’s why they’re doing the whole ‘haters – we are better than you’ thing.”

Why are the media happy when Sticky Fingers fail?

Years ago I had the news media cycle explained to me thusly: You keep a story alive for as long as you possibly can. People get tired of hearing the same thing over and over again, and a story needs to die. If something new develops on the story, you can resuscitate the entire thing with that one new thread of information.

The news cycle story of Sticky Fingers has become one for journalists of refreshing and rehashing the past and journalists leaning into implication as far as the letter of the law will allow them. As shackled as the law leaves journalists, the inflammatory Instagram posts or disastrous Hack interviews or reports of public altercations breathe fresh life into a half told story.

Sticky Fingers have now deleted the words “to all the haters, we are better than you” from their latest Instagram post, which they shared shortly after Dylan Frost was accused of being removed from a Sydney pub for bad behaviour. pic.twitter.com/A7EfNklzXN

— Tom Williams (@tom__williams) May 21, 2018

“I highly doubt the [music] industry will support them for the most part,” so says the Festival booker. “The thing for me is even though 90% of the industry and probably the majority of punters are pretty done with them now, there’s still SO much [conversation]. It’s oxygen for a band like Sticky Fingers even when it’s all bad.”

‘Open industry secrets’ and ‘rumours’

I work in the media, and let me address, in a deeply roundabout way, what I need to say about this. Yes, one harmful event, thoroughly reported on by a number of news outlets, has become the nexus point for the conversation around this band. The alleged victim of this alleged assault, has, however, now distanced themselves from acknowledging or talking about this, and has deleted the accusatory Facebook post.

Additionally to this, last week, Frost was thrown out of Kelly’s in Newtown after an altercation with a trans woman, as reported by The Australian. My Twitter feed, which is a music media who’s who (echo chamber), was alight at the coverage, in shades of what I would describe as varying from emphatic frustration to gleeful Schadenfreude at Frost’s fall from grace after the whole band’s commitment to sobriety in April.

Sticky Fingers have just released a new EP tracklist!!!

1. I Can’t Be Racist, I’m Maori

2. Boys Being Boys (Excuses)

3. I’m A Fragile Man… Let’s Fight

4. Sorry, Forget Everything

5. We Got Lawyers So Yeah— Monique Myintoo (@aumonique_) May 18, 2018

There are, however, a number of other allegations that I have been told by close friends, musicians, powerful venue bookers, of their first hand experiences with Dylan Frost. Some of them are maybe true, some of them maybe not.

“[Dylan Frost] was kicked out and banned from [another Newtown venue] earlier this year for being violent and trashed as well.’ I was told by a powerful festival booker when I reached out for comment on this article. ‘This was post the whole sobriety thing. I don’t think [the venue will] go on the record about it (common thread: big brands won’t support Sticky Fingers but they also just don’t want to be in the convo), but it absolutely happened.” This event was referenced in reporting by Goat.com.au following the band’s appearance on triple j’s Hack program.

“I don’t know if it was deliberate at first, but they’ve definitely found this groove – in terms of allegations etc. where they deny everything and threaten lawsuits.” A venue booker mused.

The paralysing defamation laws in Australia have created a partisan split of supporters of Sticky Fingers and their detractors. Their fans remain joyfully and wistfully enraptured by the band, while the media outlets who are meant to be servicing these fans publish hot take after hot take that is aimed only at industry insiders.