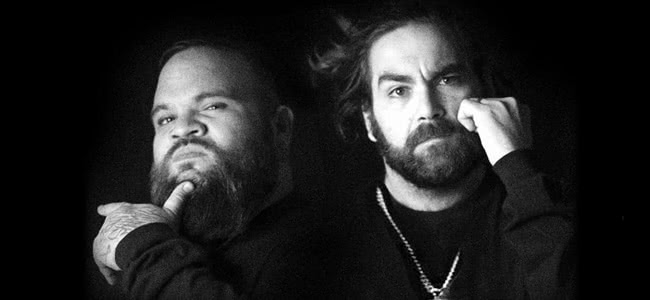

“I see a lot of white faces here tonight,” Briggs smiles from behind a microphone draped in a Lakers jersey and a Lowes Hawaiian t-shirt, “which just proves that we’re fucking right.” He cracks his golden-tooth grin and the crowd erupts into laughter. Briggs’s A.B. Original counterpart Trials chortles in unison, garbed in matching threads littered with palm trees and surfboards with a backpack swinging from his shoulders.

It’s a misty but humid Monday night in Melbourne where the Indigenous hip-hop supergroup are hosting a listening party for the collective’s debut album. Looking around the room, Briggs isn’t incorrect in his observation and he’s not afraid of pointing out the irony. Nobody is upset; in fact we laugh along with him, because we agree. It’s a tongue-in-cheek moment, but it’s not devoid of a grain of truth.

But why do A.B. Original’s detractors nit-pick and accuse them of reverse-racism? “Cause they’re mad,” Briggs and Trials snicker together when I chat to them the next day. “There’s nothing denying the fact that we have white fans,” Briggs immediately postures his tone. “Our shit wouldn’t travel up the charts if it was just our family buying it.”

“To be fair,” Trials interjects… and then the reception cuts out. “Trials?” Briggs giggles. “Where’s this dickhead gone?” Sadly, the rest of the interview was conducted without the Funkoars member and ARIA award-winning producer.

Briggs continues, “We wholeheartedly love all of our fans and all of our supporters who come out and do understand our message and do understand the importance of that message and understand that it needs to be heard and they aren’t threatened by that message because they’re strong, smart individuals.”

Take a skim through Briggs’s Facebook comments section and you’ll see there are still a large population of Australians who strongly disagree with A.B. Originals’ message or oppose their assertive tone on principle, not realising that the endgame is equality despite their animated form of expression.

“It takes too much accountability on their behalf to accept that kind of message,” Briggs remarks on those who can’t see that this everyone’s fight. “They have to look at themselves and see what their involvement entails and a lot of people aren’t comfortable with that. As we’ve seen and as we’ve found, a lot of people are. Everything takes time, everything is a shift, and everything is a movement. It’s a marathon. It’s not a sprint.”

One can’t deny though that the vehement racism and cries of reverse racism which the duo encounters isn’t dying out quickly. In the age of social media profiles where the average individual can disseminate their thoughts into the ether, does that viability embolden racists and provide a soapbox that they feel validates their misguided views? Not necessarily emboldened, says Briggs, but provide opportunity.

“It’s just another avenue for them. Some people you don’t even know if that’s what they truly believe or if they’re just trying to get a rise. If someone says something horrendously racist to me, and they don’t have a picture, you know they’ve just created this account just to say some racist shit. It’s hard for me to take that on board. I can’t give it any kind of air. Cause it’s like, anyone could have done that.”

“Anonymity is a big shield for the cowards. I’m not phased by any of that. It’s when they do have all their socials open and they are an actual person or they are an actual business that I go in and air them out. But if it’s just some random, it’s like, ‘What’s the point?’ That’s tiresome for me.The internet and stuff, you used to have write into the newspaper to have an opinion. You used to have to write in longhand even to make it in the opinion pieces. But now anyone with an opinion can shoot it out there. So it’s hard to take offence, especially if it’s some cheese ball, like whatever man.”

Unfortunately those cheese-balls are at large as blackface incidents across this country continue to stem up on newsfeeds, new channels and public events. It may feel like a recent epidemic but unfortunately it’s not a new trend. Briggs recalls the confusion and pain he experienced when he was confronted with it as a child, then how that evolved through growing into manhood.

“When I was younger, I couldn’t quite put a finger on why I didn’t like it. Cause you’re not taught in school about why blackface is fucked up. This is on the onus of a black parent now or a parent to a black child to explain to their kids why that might not feel right for them. I remember seeing it and feeling, ‘That’s not funny. This feels insulting. But I don’t know what it is. Why it makes me feel this way. I definitely don’t find this funny. It’s making me mad.’ Other people around you are saying it’s just a joke, having a laugh. But this isn’t cool.

It wasn’t until later on in life that I was able to diagnose why I found this so repulsive. It’s the nature of the racism, the disenfranchised, to dehumanise somebody to not ask those questions. The nature of this racism of being so bold, to make you feel so small, that there’s no point for you to ask these questions about why they’re doing this. Cause you’re gonna feel the ridicule of everyone around you telling you to get over it. It’s just a joke.”

Blackface isn’t native to Australia, its sprouts up all throughout Western civilisation. However while we share the same issues as other countries, our inherent tall poppy syndrome renders us blind to our own failings as a culture and society. Australians are quick to criticise America, for example, after recently electing Donald Trump as President, but not so much when it comes to voicing outrage against the current and historical mistreatment and discrimination of Asylum Seekers and Indigenous Australians. “Funny that,” Briggs bluntly snorts.

Same again when Australians re-tweet and filter profile pictures with messages like ‘Black Lives Matter’ in an American context but seem to demonstrate indifference to those same issues in their own country. Is this a product of Americanisation or is there something more sinister at play? Briggs suggests that distance is a safety net. “Acknowledging that America has a problem doesn’t take any kind of responsibility on their behalf. And they act very uppity, about how smart we are and how dumb Americans are for voting in Trump when we had Tony Abbott whose whole campaign was written around ‘Stop the Boats’; a racist campaign.”

Australia’s cultural blind-eye is also selective in remembering our past leaders. “We had a Trump. We had an extreme dude who had both houses, upper and lower, in John Howard. Australians on a community level don’t like to acknowledge the issues at home and the issues in their own backyard.” Briggs suggests that it’s an apathy which strikes all areas of Australian life. “Even the bleeding hearts who run up to the Northern Territory to find their Aboriginal experience seldom look to the kids who are in out of school in their own city. It’s harder for people to have a romanticised view about something that they can have direct responsibility for.”

Onus is a vital theme to Reclaim Australia. It’s a call-out to a nation divided to recognise our fragmented culture and society which is founded upon blood in the sand. It’s also a message of taking action, “It’s one of inclusion,” Briggs says about what role both Indigenous and Non-Ingenious Australians can fulfil after listening to this record. “This is about inclusion. This is about being conscious of putting indigenous artists on the festivals bills. Not just because they’re indigenous artists. A lot of these artists are excellent. It’s about creating.

“With Reclaim Australia, the whole idea of this record was to be so out there and have such a push and such a momentum and such a movement that it moves so far over that it can’t move back. Where we come out and we sound so extreme, when Birdz from Bad Apples comes along and he does a song called Black Lives Matter that doesn’t sound that extreme now; it’s more palatable. It felt like it was our job to not just kick the door in but off its hinges and create a funnel fare that we can all just walk through.”

By marching through that door together, Briggs and Trials are demonstrating that this album isn’t breaking a silence, it’s screaming for recognition that there never was a silence. “If it wasn’t us who what was going to be,” Briggs says of why he and Trials are stepping into the spotlight with that demand. “We just report and point at these issues and say, ‘Look at this. Look at that. Look what you’ve done.’ We shine a light on how this looks. And that’s always going to be our role as artists.”

With Reclaim Australia out today and with Australia’s first Indigenous hip-hop label, Bad Apples Music hosting a boiling pot of fresh talent in Nooky, Philly and Birdz, it’s important to recognise that this momentum shift has been a long time coming. It’s a fight that isn’t a current popular trend, Indigenous hip-hop artists like Wire MC and BrothaBlack were defiant with the same message of ‘Too black too strong’ and yet since their career fell during a time where Australia’s hip-hop in general was still largely an underground and niche movement, their voices were largely unheard by the majority of Australia.

Briggs suggests that it’s a combination of our music industry’s growth and his and Trials platform which means this type of record from an Indigenous hip-hop act is only being made now. “We grew into this album. I grew into my role. In the industry and the country. Whatever insults people hurl, doesn’t really affect me. Artists like BrothaBlack and Wire were definitely doing their thing; they were just never able to get to this level. And as soon as we got to this level it was on us to translate that.”

An element of that translation is the dialect in which Briggs & Trials have chosen to get their point across, with Briggs in the past saying, ‘Rap music in Aus don’t sound like Rap music no more.’ It’s not a niche or snobby opinion and it can be easily dismissed as hip-hop purism and elitism. It’s worth nothing that in the past five years hip-hop has finally been embraced by masses of triple j listeners but since it’s an adopted culture and artform, for Briggs the roots of the music are being lost.

“It’s about just culturally, it’s different out here for rap music and rap music worldwide has shifted over time as genres do. There was something about rap music out here, that we lean more towards a genreless pop-hybrid. With this record we really just wanted to take it back to the core values of a straight up and down, no ifs and or buts rap album. Just a rap album that sounds like a rap album.”

With its heavy G-Funk and West Coast flavours, A.B.Original have certainly achieved that. Growing up in Shepparton and Adelaide respectively as young indigenous hip-hop fans, Briggs and Trials idolised American rappers like Snoop Dogg, Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls but was it painful not seeing Australian indigenous faces on Rage as a child? “You loved all that stuff cause it’s like why do you watch the NBA? Cause it’s the best of the best. So they were the best of the best. Even if you had rappers in Australia, they were still no where even near those guys. It was a more positive affinity with them than a negative ‘What about us?’ It was a, ‘Wow! I wish I could do that!’

“We didn’t have the rappers for us. There may have been Wire and BrothaBlack but I didn’t know of them when I was a kid in Shepparton without the internet. But now with communication being so viable, every kid’s got phones, they’ve all got access, it’s a different kind of movement you can create. Yeah, they’re gonna listen to their Young Thugs and their Rae Sremmurds or whatever but also now they’ve got this other stuff from home that’s speaking about stuff that affects them. It’s just another option. What we wanted to create as artists was what we wished we had when we were kids.”

Briggs and Trials have seized the opportunity and used their platform to make what they call ‘the blackest album’ Australia has ever seen. “It’s a funny thing we’ve adopted,” says Briggs. “The blackness and the black idea when we are so many nations. It’s an overall encompassing thing. Maybe throughout my next ten years or so my approach to ‘what is the term black?’ might shift and change. But right now it’s what we’re comfortable with and what we know and what people identify with, straight away.

“As a culture we have adapted and we will adapt over time and everyone’s points of view on idea on how this will all works and how this looks is gonna be different but what I’m trying to engage is positive dialogue. In the case that okay it’s not ‘black’ in quotation marks, what’s indigenous? How do we move forward to the next step to make this truly ours? That’s just an ongoing conversation. But right now, everyone knows what we talk about when we say this is black excellence.”

What they’re saying is despite being defined in negative terms, reduced to any action or stance being a reactionary one, that they are proud of their identity, proud of their culture and proud of their land. As this nation’s first people, with centuries of unrest and torment heaped upon them, the odds are stacked, and failure is an expectation.

Archie Roach, Paul Kelly, Adam Goodes, Nicky Winmar, Gurrumul, Cathy Freeman, Patty Mills, Jimmy Little, Deborah Mailman, David Gulplil, Lionel Rose, Marcia Langton, Nathan Jawai, Linda Burney and now Jessica Mauboy, Thelma Plumm, Philly, Birdz, Nookie, Thelma Plumm and of course A.B. Original are exemplars of that excellence, of succeeding despite historical, political and socio-economic improbability.

Speaking of unlikelihood, is our country ready to make a statement, say, by voting ‘January 26’ #1 in the Hottest 100 on Australia Day?

Briggs doesn’t hesitate, “I’m a big lover of irony so that would be hilarious if that happened.” Trials voice chimes in, “The irony is not lost on us, neither will the victory be.” Then his connection drops out again. “This dickhead,” Briggs laughs. “Driving to Wolf Creek while he’s on the phone.”