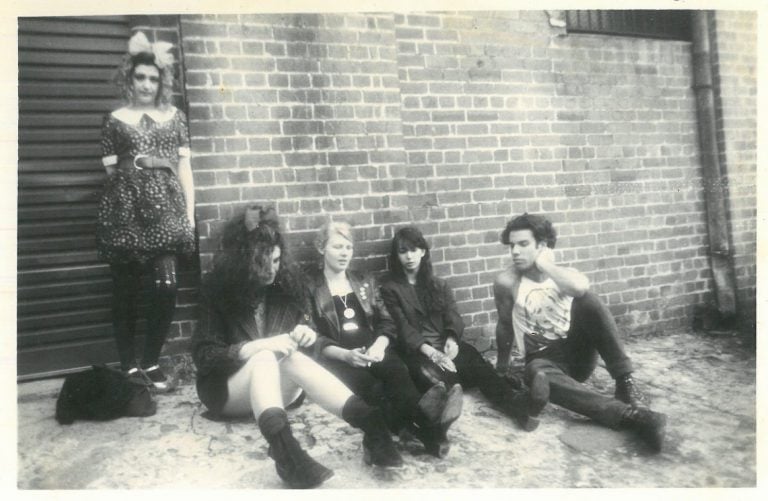

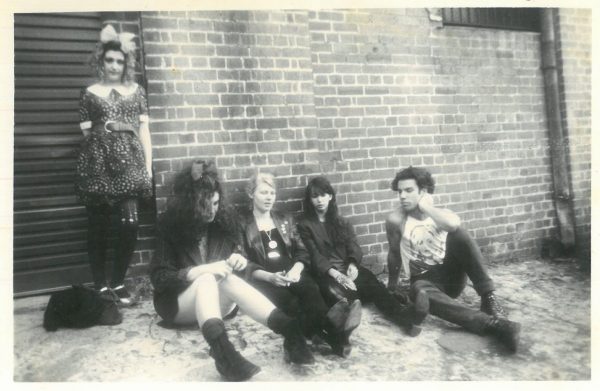

Sydney, 1988. A post-punk band consisting of four girls and a guy had the nerve to make some noise in an underground music scene dominated by men with guitars. The band, Matrimony, had some fun and made a great album called Kitty Finger that took their sound all the way into the heart of the riot grrl movement in the US Northwest, championed by Kathleen Hanna and re-released by iconic US indie label Kill Rock Stars.

Matrimony was short-lived. Less than a year after they formed, they had stopped playing and the band has left barely a trace on the Australian music landscape. But their impact on the post-punk feminist rock scene in America hasn’t been forgotten, and in December 2021, thirty-two years after its first release, Kill Rock Stars are set to reissue Kitty Finger on vinyl, CD and digital.

I first came across Matrimony in the course of researching for a novel-in-progess about a fictional all-girl band from the ‘90s who were forgotten in the general churn of Australian music. Looking to get some background on the industry, I’d found a book in the stacks of my local library called ‘Dig: Australian Rock and Pop Music, 1960-85’ written by music scholar David Nichols, who unbeknownst to me, was to be the knot at the centre of a few threads in this story.

Browsing through the book, I came across a single paragraph about a little-known Sydney band and within it were a few words that turned my head:

“… Matrimony are now considered a forerunner, if not an instigator, of the riot grrl movement.”[i]

I loved the bands of this movement, so why hadn’t I heard of Australia’s very own riot grrl band before? I couldn’t find much else on the web about Matrimony, but I did locate Kitty Finger on Spotify and it was awesome: a raw post-punk album crackling with youthful disaffection and an experimental sound that came well before the 90s grunge phenomenon.

Once I realised that they had a solid American following, I had to ask: if music fans overseas recognise Matrimony as unique, bold and ahead of their time, why are they are so criminally overlooked here?

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

Clearly, it’s time to correct the record. So, I tracked down a few members of the band and David Nichols to find out more.

Back to Sydney in the 1980s.

There were not so many women on the underground music scene. Fiona Horne’s early outfit the Mothers stood out as one of the only all-girl bands who rocked. Even so, it was a vibrant scene with a range of interesting local acts like Box The Jesuit, Lubricated Goat, Space Juniors, the Cannanes and Distant Locust playing every week at a rotation of venues in Surry Hills, Darlinghurst and Kings Cross.

Zeb Olsen was an enthusiastic young fan who wrote reviews for street press and made her way to any gig that she could get away with as an underage teen. She kept seeing the same group of cool girls on the circuit of gigs and club floors and admired their funny hair and crazy op shop outfits. “It was back when I thought that if someone looked interesting, they must be interesting,” she admits. “Sometimes I was partly right.”

Eventually Zeb and one of these girls, art school student Polly Williams, connected and decided they didn’t want to be bystanders anymore: they wanted to start their own band. So they scrounged equipment and hired out a dark, dank rehearsal room at a warehouse in Darlinghurst, the centre of queer culture and close to all the action where some of the glamorous performers they saw on stage and around the streets played and rehearsed. Zeb and Polly’s ultimate ambition for the band, says Polly, “was for girls to make some noise, have fun, dress up and hang out in the cool inner-city band scene.”

Zeb and Polly began their search for a line-up, playing with a few disinterested drummers, including a drum machine. But within a few weeks they were joined by a network of friends: Polly’s neighbourhood buddies Sybilla Visalli and Michael O’Neill, with Polly’s art school mate Dani Marich coming on board last as flyer designer and guitarist.

Says Dani, “I joined Matrimony after seeing their very first show at the Palace Hotel… they looked like a group of fabulously dressed teenagers doing a really fun, light-hearted performance. It was hilarious, the audience didn’t know what had hit them.”

The DIY spirit of post-punk was in the air. As a band, Matrimony admired the alternative sounds of The Birthday Party, all of Tex Perkins’ bands, The Scientists, the Saints and the Go-Betweens, and further afield, the art-school and punk traditions of bands like the Cramps, Velvet Underground, Lydia Lunch, the Modern Lovers and the Runaways.

They also loved the pop trash vintage aesthetic of the B-52s and bands that rebelled against the slick professionalism of the mainstream, contemporaries like Pussy Galore and Beat Happening who were in the process of changing some of the rules of underground music in America.

Closer to home, Zeb was friends with The Cannanes, a DIY indie pop group with three women in their line-up. Watching them, she was encouraged by the idea that you didn’t necessarily have to know how to know an instrument to play live. Which was great, because Polly, Dani, Sybilla and Michael had never been in a band before.

Zeb came from a musical family and had been in a few line-ups with her brother Stuart Olsen throughout her teen years. She knew her way around a bass and so Matrimony’s songs initially began with her. For example, she introduced a riff, Dani worked on chords to fit the songs and Polly plugged her red fuzz guitar into several distortion peddles.

Michael instinctively lay down drum beats to Zeb’s bass and vocalist Sybilla found melodies for her original lyrics. They experimented and mixed it up; sometimes Dani came up with an idea on guitar, sometimes Polly wrote the lyrics and new songs would emerge. They were amateurs feeling their way awkwardly through the song writing process, and in true punk style, it resulted in weird and wonderful arrangements.

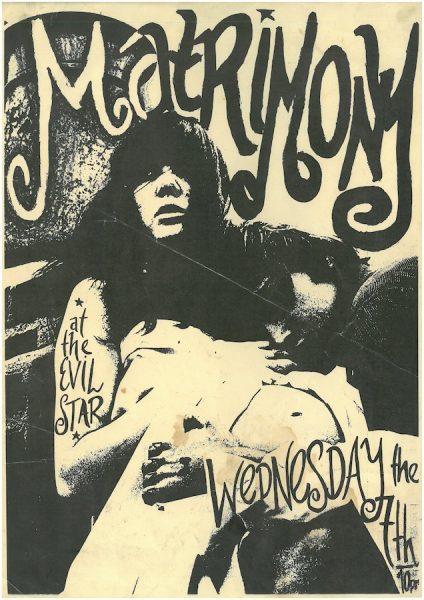

Matrimony soon started playing a few gigs at Sydney pubs and squats in Chinatown and Rushcutters Bay. They were having a great time. “But we were not great live,” laughs Zeb. “We fucked up and got drunk, we were a mess.”

She realised they’d shaken up the status quo when she got bailed up in the toilets by two angry women after a show, asking her why they were doing this sexy bullshit. What you’re doing is not feminist, they insisted. “It was very confronting being criticised by other women like that,” Zeb admits. “Were they jealous? Were they too scared to start their own band? It was confusing.”

Matrimony was getting some buzz. In a 2001 interview, Matthew Bright from Distant Locust (and the producer of Kitty Finger) recalls how radio station 2JJJ pronounced that Matrimony would be one of the great bands of the next decade. “They were unique for their time. Something exciting about them, something sexy… they appeared to not have a clue about what they were doing. They were genuine inheritors of the punk ethos of just getting up there doing it.”[ii]

Enter David Nichols, author of ‘Dig’, where I first saw Matrimony mentioned. At the time, he was a drummer for the Cannanes and the editor of Smash Hits, who happened to have access to a wad of petty cash from selling review copies of albums to record stores. It was usually spent on frivolous staff lunches, but this time the team decided to do something more serious with the money. David knew of Matrimony through his friend Zeb and suggested to the team that they bankroll a recording project for them.

He is careful to put quotation marks around the word ‘investment’. “No one ever saw any money from it,” he says. “We all had short attention spans at Smash Hits. We decided to invest in something fun but didn’t know how to see it through. It was a free money opportunity. All care and no responsibility.”

Most of the band didn’t even know who David was. All they knew is that with studio time and record pressing covered, they were making an album. For a few months they focused all their efforts rehearsing at Drive in Art, a friend’s squat in Rushcutters Bay, learning all their parts at home and coming together to perfect the arrangements, build camaraderie and hone their musical skills.

Kitty Finger was recorded in ten hours on a winter’s day at Fat Boy Studios in Sydney. Fifteen languid songs set to freewheeling music emerged, with one cover; Frantic Romantic by the Scientists. “When we went into the studio, it was magic,” Zeb recalls. “We oozed confidence and only had to do one or two takes of each song.”

For Dani, the whole experience felt like a fantasy, she couldn’t believe it was happening. “I distinctly remember listening in the control room while Sybilla’s vocal tracks were being recorded and thinking ‘How the fuck did I get to be included in this group?’ It sounded so good.”

While the songs were the results of everyone’s collaboration, they were mostly put together but the dynamic song writing duo of Zeb and Sybilla, whose lyrics were quick-witted and poetic with a pop-trash aesthetic, full of youthful nihilism, lust, Catholic guilt and Andy Warhol references.

Matthew Bright produced the album. “He had a ‘thing’ for girl bands,” says Polly, “and set about creating a ‘wall of sound’ for the album, layering my distorted feedback from the fuzz guitar and perfecting Matrimony’s lo-fi feel.”

Zeb’s brother Stuart, intern Anthony Keena and studio engineer Cameron Howlett were there to help mix the album. “I know it wasn’t very feminist with all these guys in there with us, but they were great. They didn’t impose, they knew our songs and they had total confidence in us. It really helped,” Zeb remembers.

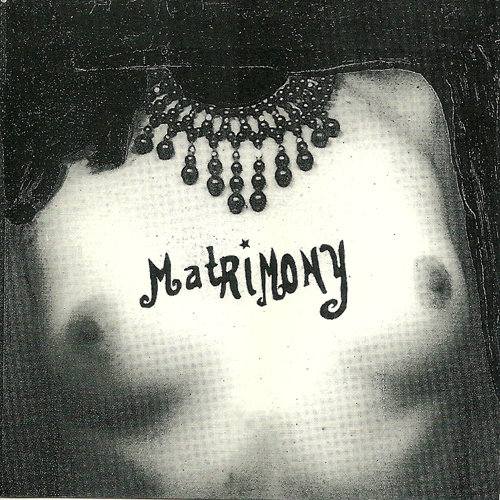

The album was named Kitty Finger after a found image of a little girl demonstrating a pose in a 1970s book about yoga. A bold photo of Sybilla’s bare, beheaded chest, taken in a $2 photo booth graced the album cover. David Nichols and Zeb Olsen oversaw the 1989 release of the album on the independent label Frock productions and it was distributed through Waterfront Records in Sydney.

No one remembers exactly how the album made its way to Olympia, Washington, USA in 1989. But no doubt it had something to do with the informal underground distribution network between Australia and Washington state. Back to David Nichols again. For a few years, he’d been corresponding with Calvin Johnson, founder of Beat Happening and the indie label K Records, in which they exchanged letters, zines and tapes[iii].

Thus, David was inspired by the Olympia scene, and also played a big part in sharing Australian music culture with his connections in America. It was through this network that Kitty Finger preceded Zeb’s visit and influenced everyone in town with its lo-fi minimalism and punk ethos.

“All I know is that when I got there, Kathleen Hanna had already heard Kitty Finger and loved it and she really wanted to meet me” says Zeb. This was the second trip she had taken to America in 1989. The first time had been with David Nichols, where, on her first day in Olympia, she’d met her hero Calvin Johnson and he invited her to play music with him. She couldn’t believe it.

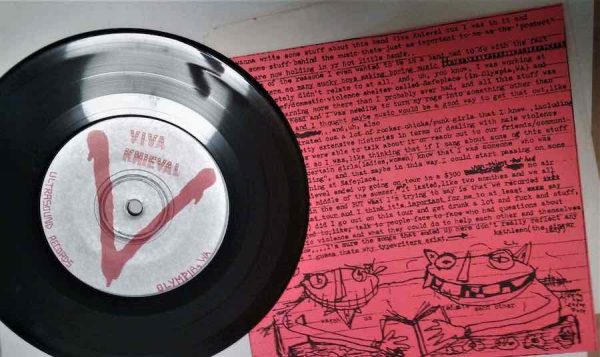

“Olympia was a transient college town with an ephemeral grassroots scene,” says David, who had spent a lot of time there in the 1980s. “It was a very creative time. There was a sense that creativity was a form of resistance against broader society.” Zeb, her brother Stuart and David had been swept up in the scene and played with a wide range of local musicians, including Tobi Vail, Kurt Cobain and Billy Karren, in a bunch of recording projects with bands like the Go Team and Some Velvet Sidewalk and Viva Knieval, which was to be Kathleen Hanna’s first band.

There were similarities between the two far-flung creative music communities in Australia and the Pacific Northwest of America, with both scenes mostly dominated by white men who developed a unique loud guitar sound characterised by feedback and other noise effects. But in Sydney, the collaborative music culture wasn’t as accessible for girls in bands: they didn’t have the same opportunities to form, play for a while, break up and reform in new configurations as a means to developing their skills in music.

“I always felt like we were pushing shit up hill,” Zeb admits. It didn’t help that Sydney was awash with heroin by the late 1980s. “It was a grim time. All the bands we loved were doing heroin, all my boyfriends were junkies. It was good to get out and go to America.”

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, there were the rumblings of an underground movement called the riot grrls, a groundswell of young women fighting against patriarchal dominance and all the damage it entailed.

It was from within a macho music scene and a culture of creative resistance that a passionate and active feminist like Kathleen Hanna felt assured in her desire to start a band in the face of “so many sucky boys making boring music.”[iv] The movement expressed itself creatively with countless stunning zines, happenings and bands like Bikini Kill, Heavens to Betsy and Bratmobile.

Unwittingly, Matrimony’s Kitty Finger had arrived in Olympia at just the right moment to lay the groundwork for all this. But it took someone like Kathleen Hanna, a forceful advocate for women, to recognise their uniqueness, shout their name and tell everyone how cool they were. Hanna continued to champion Matrimony and it was at her urging that Bikini Kill’s own inclusive and artist-friendly record label, Kill Rock Stars would release Kitty Finger on CD in 1997.

“Every time I listen to the Matrimony record I get super inspired,” she wrote to the group in a letter, “and maybe some other girls will feel the same and start a good band for a fucking change.”

Back in Sydney in the early 1990s, Matrimony hadn’t formally split up. But Zeb’s absence and a tragedy in Sybilla’s family left things up in the air. Sadly, Sybilla started to spiral out of control as she dealt with her personal trauma. She became mixed up with some notorious older guys in the scene and was introduced to hard drugs.

Her friends tried their best to help her navigate her grief, but they were just kids without the experience or resources to save her. Michael, Polly and Matthew Bright had been hanging out with Sybilla just hours before she died by suicide in 1992 at the age of 22.

“Her death affected us deeply. To this day, her passing is still dramatic, confronting, confusing and sad. She haunts us every time there is Matrimony business,” reflects Polly.

From her point of view, Sybilla’s death is connected to that spectre of would-be rock stars on the Sydney scene, some of whom went on to pursue successful music careers overseas. “Looking back through a feminist lens,” she declares, “a young girl’s life was sacrificed.”

The band all agree that Sybilla’s death was symbolic end of Matrimony. Nonetheless, Kitty Finger prevails. These days, Matrimony’s guitarist Dani runs the Kitty Finger Facebook group and each surviving member of the band has their own archive of artefacts and memories.

“I have always felt that Kitty Finger has a life of her own,” Polly says about the album that refuses to fade away. “She produces her own success. Every decade since its release the album has roused some sort of interest. She is a document of our youth. Over thirty years later, Kitty Finger still sounds fresh.”

[i] David Nichols, “Dig : Australian rock and pop music 1960-85.” Portland, Verse Chorus Press, 2016. Page 485.

[ii] Bob Blunt, “Blunt: a biased history of Australian rock.” Prowling Tiger Press, 2001. Page 155.

[iii] Jon Stratton, “The Scientists and Grunge: Influence and Globalised Flows.” Australian Rock: Essays on Popular Music, Network Books: Perth, 2007.

[iv] Kathleen Hanna, Viva Knieval liner notes, Ultrasound Records, Olympia, Washington, 1990.