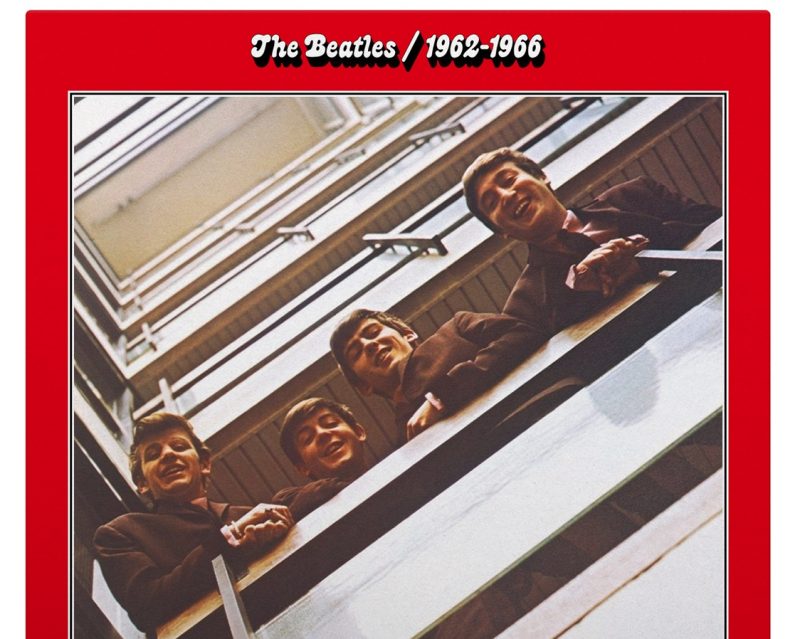

You never forget your first time. It’s May 11th, 2004, my ninth birthday, and my father hands me a tightly gift-wrapped present. Inside is The Beatles 1962-1966 CD, or the Red Album, and it’s the first piece of music I can treasure as my own.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that it was life-altering. Until that moment, my youth had been soundtracked by the ubiquitous and cultishly commercial Now That’s What I Call Music! compilations – without the exclamation mark we weren’t to know that it was music that mattered – and the previous year, I had received one that opened with a Black Eyed Peas song and finished with a schmaltzy cover of ‘Mad World’.

But then I received the Red Album CD and my world was audibly opened up, and I began to collect as many notable CDs as I could. Later I would find out that my father had gone through a similar moment with my grandfather when he was handed a solid stack of Beatles 7” one day and a lifelong obsession was born.

My grandfather was a man firmly of his generation, made of few words, ravaged by unspoken inner turmoil from his mining days, but he was transformed when he would play The Beatles for us grandchildren on weekend visits, his eyes lit with unfading memories.

Those 7” vinyls – now very dusty but never unloved – are still in my grandfather’s house, my father electing to leave them there when he moved out of his family home.

Six years ago, when I left Scotland for New Zealand and saw my father in person for the last time, I took a lot of possessions with me, including many cherished music CDs, but I left that Beatles one behind with him. The CD will be waiting for us to play together when I finally return home.

This passage has just been a convoluted way of conveying the opening message: you never forget your first piece of physical music.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

The digital age has done many things for music, many good things, but it has taken away such distinct moments. I cannot remember the first song I streamed on Spotify, or even the first song I downloaded on LimeWire; I have no doubt you’re the same. Our listening experience is more convenient but far less momentous.

It’s not just music. Just this week it was announced that Warner Bros. Discovery was removing many titles from its streaming platform HBO Max, including major series like Westworld. On social media, the reaction took on an almost mournful atmosphere. Artists and non-artists alike were dismayed and depressed at the realisation that these titles, without backup physical media, would become completely lost.

In other words, physical media matters. When art is in the hands – and decision making – of callous corporate charlatans, it matters even more. It’s wildly ambitious to envisage the entire industry changing overnight, but what’s needed in 2023 and beyond is people with power doing something to preserve media properly.

Mark Alexander-Erber has that power as the founder of The Golden Robot Global Entertainment Group featuring their main label Golden Robot Records. “We feel for 2023 and beyond that as a label it’s Golden Robot’s responsibility to do even more for the bands on our roster to find more ways to attract and keep the fans involved,” he tells Tone Deaf.

“One of the ways we’re doing this is by investing even more into physical media that we have previously, especially vinyl, for more of our artists so their fans can feel a deeper connection to the music, providing them with more of an immersive experience directly related to the band.”

With just under 500 bands spread across 12 global record labels, it will be a mighty task but a fundamentally important one. That’s why it won’t just be Golden Robot heavyweights like Riley’s L.A. Guns, Filter, The Answer, Frank Carter and the Rattlesnakes or Jefferson Starship getting the physical media treatment.

“Usually we only do this for bands that can sell in retail stores globally, rarely outside of this scope but from next year we want to try and do this for all bands where possible, even the young bands starting up. We want them to secure a fan base early in their careers by involving their fans even more from their first EPs or debut albums. We want the fans to feel touch and be part of the bands’ legacy.”

As Alexander-Erber puts it, digital platforms as important as they are like Spotify and iTunes are “too clinical”. A vital sense of connection is lost in the binary wilderness and certainly Covid didn’t help almost wiping out a tactile or personal physical approach for many years.

“We want the fans to feel more connected to each of the bands on the Golden Robot roster by experiencing what it’s like to unpack and listen to a vinyl exactly the way bands in the ‘70s would make you feel,” he adds. “It’s a real organic connection to the band that hopefully makes you a lifelong fan wanting more. Have you ever sat and opened Physical Graffiti By Zeppelin or Exile on Main Street by the Stones? If you have you will know exactly what I mean.

And in case you’re wondering, Alexander-Erber’s first CD was John Cougar Mellancamp’s Scarecrow in ’85 and his first vinyl was AC/DC High Voltage in ’76.

And isn’t that the point of all of this anyway? We all started listening to music to feel ourselves inside the words and the world of our favourite artists; there is no joy to be found in looking at art through data and figures.

So while people like Alexander-Erber try and do their bit to enact change, perhaps you can also do yours: go to that record store you continuously walk by this weekend; buy the physical copy of your favourite 2022 album or even that’s 70’s album as a gift for Christmas. Maybe then you’ll be writing about the profound impact a vinyl or CD had on you one day.