Live music is a regenerative industry, and it’s arguably something we need more of now than ever in Australia.

In Steven Mithen’s The Singing Neanderthal, the cognitive archaeologist lays out the fundamentally symbiotic nature of humans and music. Before there were people as we know them today, before there was language even, there was music.

Our prehistoric ancestors, Mithen areuges, may have communicated through “a prelinguistic musical mode of thought and action.” We sung our emotions, danced our feelings, and collectively performed our lives to a harmonious rhythm. Music was not only woven into the fabric of human society, it is perhaps the very origin of social cooperation. Indeed, it may have been our musical capabilities that made us the most dominant species on the planet.

The story of humans is inseparable from that of music. Professor Sarah Wilson, cognitive neuroscientist and president of the Australian Music and Psychology Society, says that humans are a musical species, perhaps more so than a linguistic one.

“When we look at child development, music and singing kind of precedes speech and language development,” Professor Wilson explains. “When comparing language and music activity in an MRI machine, we can see a much broader activation of the brain for music tasks than we do for language.

“Language is much more lateralised… whereas music is bilateral, it’s more broadly represented. And I think that’s because of the nature of music”.

“When comparing language and music activity in an MRI machine, we can see a much broader activation of the brain for music tasks than we do for language,” says Professor Sarah Wilson

Far from being some by product of other adaptive traits – like pornography or a desire for chocolate – music is too different from anything else we do to have been an accident. Going to a gig involves almost all of our cognitive processes. The auditory system processes incoming sounds, memory holds the melodic lines, the timing system understands beat and rhythm, and the emotional network is charged across all of these. At the same time, motor skills come into play as you dance, while social interactive processes work to understand those around you.

“It really is a direct path into the reward system and dopamine activation, probably also oxytocin,” Professor Wilson explains.

“It often allows people to explore really complex emotional experiences that are hard to put into words. It has really good benefits for altruism and empathy. So you can see why it might have been kept, from an evolutionary point of view, and passed on as an important skill.”

To understand what people would be like without music is something that Professor Wilson says would be impossible to study as it would not make it past any reasonable ethics committee. “One would hypothesise that many people would see a real dip in their mood,” she says.

Unfortunately, that isn’t a hypothesis for many of us. In March 2020, live music was the first industry to fall victim to the coronavirus. 18 months later and the pubs, clubs, and dance floors across Australia have had only brief respite from the crushing emptiness of lockdown.

Pre-COVID, the live music industry employed 65,000 people and helped to generate $15.7 billion per year. The day the music died – Friday 13th March 2020, when Prime Minister Scott Morrison announced a ban on live events above 500 people – $100 million in wages were lost in the first five days. Across the whole year, that became $345 million. In March of this year, almost 70 percent of small businesses working in live music were reporting 100 per cent drops in revenue. Three quarters of those surveyed said they weren’t sure if they could last another six months of COVID restrictions.

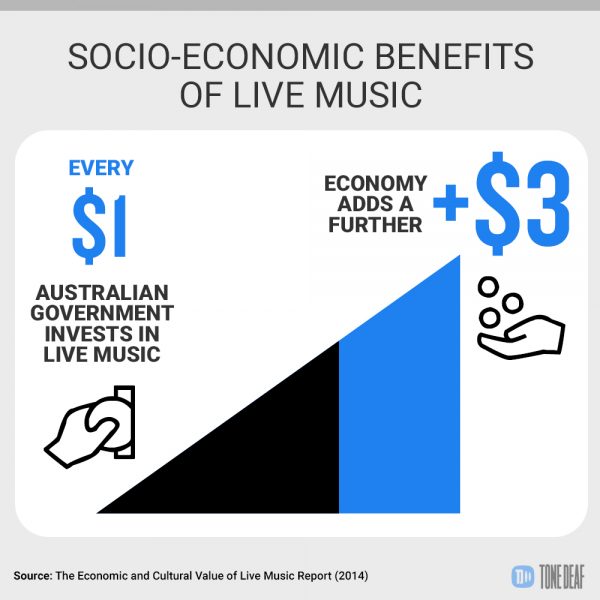

We know that live music is a regenerative industry. Aside from the cultural and social benefits of live performance, for every $1 invested in the Australian music industry by the government, a further $3 makes its way into the broader economy.

You buy a ticket to a gig, you help the band and the venue. You buy a beer at the show, you help the venue and the breweries. You buy some merch after the performance and you help multiple artists and manufacturers. That doesn’t even factor in the Uber you took to the gig, the meal you had afterwards, or the new dress you bought for the show. Live music alone in Australia contributes about half of what sport, in its entirety, brings to the economy, to say nothing of record sales and licensing.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Australian Government has committed a total of $507 billion in direct economic support, jobs programmes, and tax and financial restructuring to keep the economy and the country afloat and ensure a strong recovery. You would think that with an industry the size of live music, with such a huge knock-on effect to the rest of society, the government would be doing everything it could to support it.

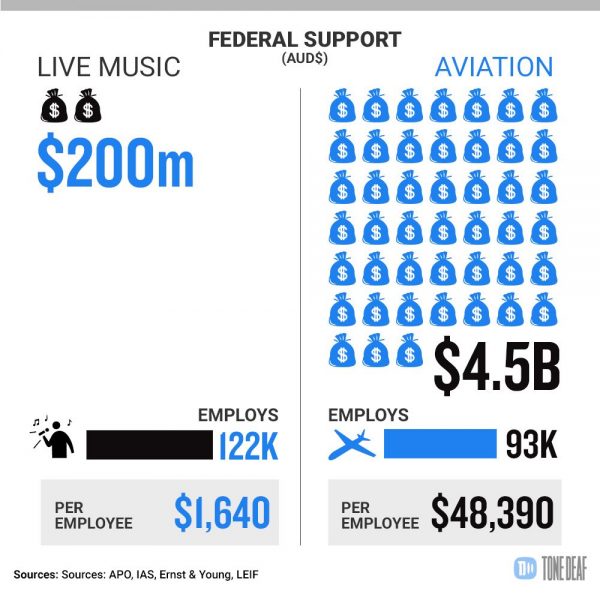

In 2020 the government committed $75 million to support live music through specialised funding programme known as ‘Restart Investment to Sustain and Expand’ or ‘RISE’. A further $135 million was added to the fund in March 2021. Over the past 15 months, while artists and musicians struggle, $40 million of that money is still tied up in the fund, with extensive criticisms over the way in which it has been portioned out. No money left the fund until October 2020 and industry leaders said it was far too small and bureaucratic to support such a vital industry. Big venues like the Sydney Opera House have taken the lion’s share of the money thus far, leaving very little, if anything, for those at the bottom who make up the foundations of the industry. Guy Sebastian, who fronted the campaign for the programme, later said he was “embarrassed” to be associated with it.

While the government has not outlined the total expenditure of support for each individual industry, we can see a stark comparison between support offered for aviation and live music, two of the hardest hit industries by the pandemic.

Some of the greatest artists in the world hail from this wide brown land. AC/DC, Kylie, The Bee Gees, Crowded House, Nick Cave, Tame Impala, Sia, Iggy Azalea, Midnight Oil, Courtney Barnett, Flume, Powderfinger. I could go on (and on) but the point is; music not only makes a nation great, it defines it. We understand ourselves through the artists and the musicians whose songs and stories become our own. It’s hard to overstate how crucial music is to a national identity.

Much has been written on the struggles of musicians in the COVID-era. The next generation – hell, even the current generation – of identity-crafting artists have been brought to their knees during the pandemic and the long-term implications of this are dire. But for us as punters, we’ve lost a huge part of what makes life so special. Seeing a certain band or an artist perform live can rank among the highlights of our fleeting existence on this planet. Those pivotal moments become the memories that make up the tapestry of who we are. Being able to say ‘I was there’ matters not only for who we are but for our mental wellbeing too.

The formation of identity trickles up through the individual before it becomes a matter of national significance. For many people, the experience of live music shapes and gives purpose to our lives.

Sebastian Alvarez is a photographer, videographer, and a musician who has been performing and immersing himself in music since he was a child.

“Everything was always decision-based around music,” Alvarez explains. “Everything that I do has to have a soundtrack attached to it.”

Growing up in Casula, in Sydney’s West, Alvarez speaks of isolation during childhood and the “click” that discovering live music had for him.

“That musical scene just pulls you together and then, next thing, you’ve got a band of brothers. All of a sudden there are these like minded people enjoying the same thing. Once you discover that, it changes you automatically. You feel like you’re part of a community.”

Lockdown put a sudden stop to the in-person community of the music scene and Alvarez, contemplating a necessary career change like so many others, “couldn’t come up with any alternative”.

“It always had to be this and there are no exceptions.”

Music is not only, as Professor Wilson says, a pin point for “really key aspects of who you are, how you connect with your broader culture, your values, and your autobiography”. It’s also a tool by which we navigate difficult and uncertain times.

Music is a tool by which we navigate difficult and uncertain times.

In 2018, David Joseph’s mother was diagnosed with brain cancer. At the time he was living in Sydney, but with his only parent in need, he moved back to his “working class” suburb of Brisbane to care for her. At the time, Joseph was “not particularly” interested in live music, having rarely been to gigs before. He describes the “not particularly pleasant” experience of cooking, cleaning, and caring for his mother as she underwent chemo as not too dissimilar to lockdown and not something he was emotionally prepared to handle.

“I had this one good friend, Patrick, and he said, ‘why don’t you come out?’ You know, go to a gig. There was a DJ playing at this club and I thought ‘yeah, I need to go out, let off some steam’,” Joseph explains.

“Just going there, the music, and being with friends, it was a little bit of an escape. It was a perfect outlet for an otherwise quite sordid situation that I couldn’t really find in anything else”

Joseph began regularly attending gigs, forming friends, and developing a whole new side to his identity that he hadn’t previously known, all the while being able to better cope with his mother’s diagnosis.

“By the end of it, when my mother was more or less recovered, I was a completely different person. From what was, at the start of illness, a kind of an outlet for the stress, at the end it was now something I had absorbed so much of that I really appreciated it.”

“I was inspired by those moments when I was feeling really down and that’s something that I hope someone can access as well.”

The line between want and need is hard to define when it comes to music but there are undoubtedly people for whom the deprivation of live music has been a bigger hit than others. For Ivy Outram, music is, quite literally, medicine.

Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, Outram uses live music both as a benchmark to gauge her manic episodes and as a motivating “carrot” to encourage her out of her depressive ones.

She recalls a particularly vivid moment at a music festival that she feels was potentially life saving.

“I had attempted suicide. I’d been put into a psychiatric hospital. And I had Splendour coming up. I got out of hospital like a week before it was set to happen and I sort of thought ‘do I go?’ I was in such a bad place but I started going ‘oh, no, I owe it to my friends to go and hang out with them’. I sort of thought ‘oh, this could be my last chance to hang out with them’ and sort of say goodbye, in a morbid way.

“I went and I was watching Slumberjack and the song ‘RA’. As the drops happened, it was just like this almost out of body experience. The atmosphere was just electric and, you know, I felt, just for a moment, like this is worth living. This is something worth living for”.

“It took four or five months to get out of that particular hole that I was in and I would look back on that moment, and watch the videos that I took from that night, and I would just sort of think, ‘Yeah, this gives you that something to live for, that that little carrot of just pure joy’. No expectations, it’s just a joy”.

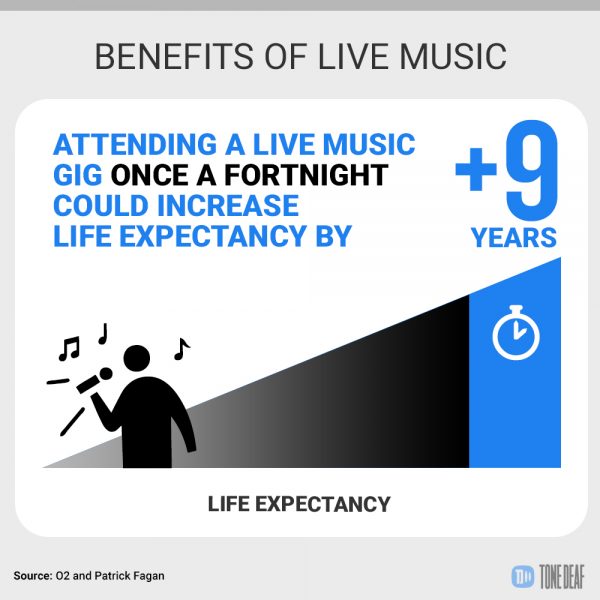

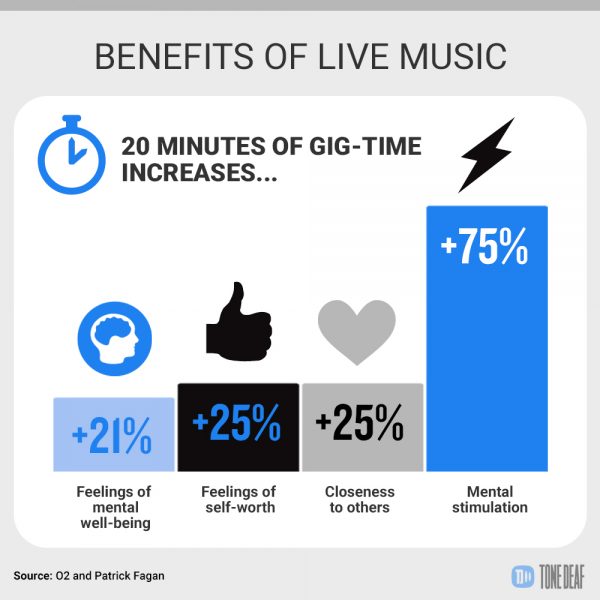

Attending a live music gig once a fortnight could increase life expectancy by nine years. 20 minutes of gig-time results in a 21% increase in feelings of wellbeing. Feelings of self-worth (+25%) and closeness to others (+25%) whilst mental stimulation climbed by an impressive 75%.

Those who attend live concerts once a fortnight and more were the most likely to score their happiness, contentment, productivity and self-esteem at the highest level (10/10), 67% of those surveyed said experiencing live music makes them feel happier than simply listening to music at home.

Those who attend live concerts once a fortnight and more were the most likely to score their happiness, contentment, productivity and self-esteem at the highest level (10/10).

Music as medicine is nothing new but its impacts are profound. There is a whole subset of psychology that uses music as a therapeutic tool. Dave Anthony is a registered music therapist who practices at recreativ mind:health and works with adolescents suffering from extreme psychosis, depression, and with suicidal tendencies in a psychiatric hospital.

He explains how music is a “perfect therapeutic tool”, with mirror neurons in the brain that facilitate empathy and connection as we see others perform a task being used to draw otherwise silent patients out of themselves.

“People who have mental health needs, who are really caught up in their experience of depression or anxiety, they are hyper-vigilant, where they go into their own body and distance themselves from other people.”

“Music really requires us to listen and express at the same time so it’s an amazing skill set to build up. I don’t know of any other modality that requires that connection and that sensory multitasking,” Anthony says.

“I don’t know of any other modality that requires that connection and that sensory multitasking,” Dave Anthony, registered music therapist.

Through engaging his clients with songwriting, Anthony allows them a space to externalise their trauma, giving them distance to reflect on events and change their own perceptions of their experiences.

“Music regulates us,” Anthony explains. “Listening to it, attending live performances, playing it, regulates us up or down. It can help us through trauma or it can help us to feel elevated and excited.”

Anthony speaks at length on the seemingly unending ways in which music has a positive impact on the mental health of his patients as well as anyone else lucky enough to engage with it. His affirmations of the benefits on our emotional well being, our immune system, our sense of identity and purpose, our feelings of empowerment and recognition of personal worth are unending. He’s not alone.

Every person spoken with for this piece has no limit to the advantages that music has brought them or society more broadly. Live music builds and maintains strong, positive cultures with a high degree of empathy and social connection to one another. This is arguably something we need more of now than ever.

Every person spoken with for this piece has no limit to the advantages that music has brought them or society more broadly.

Even in the depths of lockdown, while all the venues were shuttered and people confined to their homes, they found a way to engage collectively in live music. Virtual choirs sprung up immediately, gigs went online, and people took to their balconies to share songs with one another.

“That’s what I love about the human species,” Professor Wilson says. “They just find a way around because these things are very innate. This is hardwired into our brain”.

Graphic design by Sarah Bryant for Tone Deaf.