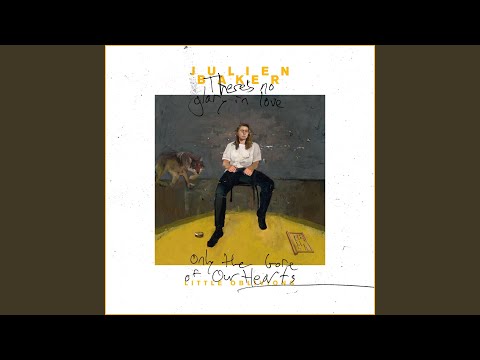

The third album from Julien Baker, Little Oblivions, was released today, February 26th, and we spoke to the singer-songwriter to discuss it.

Julien Baker’s first two albums, 2015’s Sprained Ankle and 2017’s Turn Out the Lights, established her as an emotionally intense lyricist of note. The self-titled 2018 EP with Boygenius, a collaboration with fellow rising stars Phoebe Bridgers and Lucy Dacus, prompted increased media attention.

A familiar thing then happened to Baker: a busy tour schedule inevitably led to burnout before she enrolled at Middle Tennessee State University, requiring a break from music; a similar thing happened to the Fleet Foxes’ Robin Pecknold, who removed himself from his band away to Columbia University before returning six years later with his best two albums to date.

On Little Oblivions, it’s clear that Baker has followed Pecknold’s feat. Her third album is her strongest yet and from its first fuller notes, it’s clear that the album boasts a bolder and more expansive sound. Thickening drum machines and swishing synths enhance the songs, placed amidst booming choruses and shattering rhythmic sections. Her pure confessionals are now filtered through a rockier style than the indie-folk label she was often pinned under earlier in her career.

Some of the intimacy may have been lost but her songwriting remains as admonishing and raw as ever. Little Oblivions is another reckoning with the darkest interiors of the self; few of her modern contemporaries are as brave at facing their own demons as Baker is. “Blackout on a weekday / is there something that I’m trying to avoid?” she questions on ‘Hardline’, unrestrained and unfazed. She has gone from the young girl listening to Elliott Smith and Soundgarden and not fully comprehending their pain and substance abuse to the 25-year-old artist who’s now gone through these same things; there’s a sense of weighty responsibility involved in this crossover that isn’t talked about enough.

If Baker’s way of writing is a supremely unrelenting act of excavation, she is the same as a conversationalist too. Each question I ask is clearly thought over so as to ascertain the truest possible answer; it’s a refreshing dynamic to be part of. When we discuss substance abuse, she is self-aware, acknowledging the importance of her position as an artist now as her level of fame grows. Just next week, she’ll take part in a mental health livestream alongside Dr. Mike Friedman and My Chemical Romance’s Gerard Way.

It’s ironic that Little Oblivions is Baker’s ‘rock’ record, because this expanded sound is suited to larger venues just when performing in such spaces has never seemed so far away due to COVID-19. You never forget watching for the first time Elliott Smith perform his heartbreaking song ‘Miss Misery’ (it was featured on the soundtrack for Good Will Hunting) onstage at the 1998 Academy Awards, fully uncomfortable in a white suit, the beauty of his sparse acoustic guitar lost amidst the empty spectacle of Hollywood.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

Is Baker unconsciously preparing for her move to this level of fame? For if we can say that 2020 belonged to her Boygenius bandmate Bridgers, we can also claim that 2021 is set for Baker to claim as hers; certainly Little Oblivions will cement her position as one of this generation’s strongest and sincerest singer-songwriters.

Julien Baker’s Little Oblivions is out now via Matador and Remote Control Records. She also has her first streamed concert in support of the album on March 25th, which you can purchase tickets for here.

‘Hardline’ by Julien Baker:

TD: The album was recorded pre-covid? How was it having this thing ready to put out into the world and then suddenly having a pandemic stop it in its tracks?

JB: I mean, super disorientating. We had to push plans for release and touring back. I also found it bizarre because I wrote this record in excitement to finally be playing with a full band and all of the shows that we’ve been able to play have been like radio sessions or the remote captures. I’ve been grateful for them to get to meet up and make music with these players that I love so much and who are dear friends but it’s so sterile compared to a live show. It’s just much different than I had imagined, finally making the record that called for a full band and then only getting to play those things in a studio context.

TD: It’s disorientating in a way.

JB: Yeah, it is disorientating. There’s no body language from the crowd, there’s no ongoing conversation and to me music is such a communal exercise that it seems bizarre to play a show to just two camera guys. It’s very difficult to replicate the energy.

TD: So did you always feel more comfortable in the live setting then? Before COVID?

JB: I thought I didn’t because I have such terrible stage fright. Seriously! I also think that had to do with the way I was performing and that’s another reason I was so excited about performing this album because when I was performing the previous two records it would be largely myself, just making all the loops.

Not only am I then responsible for all the sounds and I’m stressing out about hitting the wrong note, I’m also the only body onstage. It’s extra pressure because people are hyper focused on you because you are the only thing producing sound. So that’s another reason I was excited to play with a band again. I performed on a tour with Boygenius and that was the first time I had played with a band in years.

TD: It’s interesting because the record definitely does feel like it has a fuller and more expansive sound. It reminded me of how Elliott Smith moved closer to rock as he got deeper into his career.

JB: Thank you, that’s a huge compliment. I’m an Elliott Smith stan. I’ve been thinking about this a lot, like why now? Why switch sounds now? Why haven’t I done it previously on a record? I think it’s because I didn’t expect my first record to do very well. I was still actively promoting the full band I had been in since high school and college and still booking tours for them and relentlessly promoting. I was expecting that to be my primary occupation. And when that didn’t happen I felt challenged by the minimalism of this new songwriting process and also I was in a feedback loop of what people tell you you are and what people take from your music.

I was very young and I was apprehensive about making too drastic of a change. So having the time away from touring, going back to school and figuring out who I was as a person when I wasn’t being Julien the performer, that was empowering to me. I don’t want to feel beholden to embody a preconceived notion that people have of me as an artist. I’m a dynamic human being and I’m allowed to change and I shouldn’t value my worth or success based on how people react to that change.

TD: What song on the album do you think fully realises this new, fuller sound?

JB: Maybe ‘Hardline’. I want people to hear that song and think, ‘that person listened to Manchester Orchestra when they were growing up!’ Because that’s exactly what it is, I’ve always had an affinity for these guitar-driven, emotionally dynamic songs.

TD: Kind of like Modest Mouse too.

JB: Exactly. It felt so good to let myself make that song the way it was. It felt so good to not be apprehensive about it and not bring into consideration how a previous audience would receive a song like that.

Check out Julien Baker’s full performance Live on KEXP:

TD: So where did the album name, Little Oblivions, come from? To me, it seems to encapsulate a particularly rough day of drinking that you’re just happy to survive.

JB: I don’t want to over-intellectualise a thing that might not be as serious to other people but what is it that makes us have those rough days of drinking? The things that we’re chasing with substance abuse or with negative coping mechanisms or with codependency in a relationship. Or even me with running: I had been sober for many years and I would go on runs to deal with my anxiety. I was running so much at one point on tour that both my knees were completely broken yet I was still running. I would cry while I was running because I needed something.

There are so many things we use to create these moments for ourselves where we are free for a limited time from the pain of existence. Life, as it turns out, is pretty painful (laughs). This record is just a catalogue of how I seek those things out and what results it’s had on my life.

TD: I’ve been curious about the editing process of your songwriting because your songs come from such a deep and raw emotional place. How many first drafts will make it on a record?

JB: With the music, infinite edits, but only because I feel particular about that aspect and I want to make it as good a performance as it can be. With ‘Faith Healer’, there was a whole bit that was in a completely different time signature and had a different feel and different dynamic. With the lyrics though, I try to inhabit a place of acceptance with what I write initially. Obviously I edit things down, I’ll save things in my notes and I’ll repeatedly come back to them and some songs just take a little more time germinating to become songs.

I try to be sensitive to the things that I say on impulse that might be very true things and I try not to censor them. ‘Hardline’ is a great example but if there’s a lyric that I sing in a demo version in a song and realise it’s kind of cringey – not because it’s corny but just because it’s very revealing – I try to challenge myself to leave those things in there because those are the most salient parts of the writing to me.

‘Faith Healer’ by Julien Baker:

TD: That’s interesting speaking about leaving the truth of it in a song. Do you ever think back to the music that you listened to when you were younger – grunge bands, emo bands, whatever – and it would openly talk about substance abuse but you were too young to really comprehend what it was actually about?

JB: Weirdly enough I was actually just thinking about Nirvana and this. There was this song I had of theirs and I had the lyrics printed out and posted on my wall about sniffing glue or shooting heroin. And I was like 12 years old so I had no idea what it meant. I’ve thought about this so much because I find myself now at the opposite end of responsibility. I’m not a child without experience looking at artists that are speaking about substance abuse, I’m an artist with experience of substance abuse wondering how it will influence the people that listen to my music.

What I think attracted me so much to artists like Kurt Cobain or Chris Cornell was that even if I didn’t have a relationship with substances, I could tell that they were using something to medicate a pain that they felt. And I felt similarly, I had this unexplainable mental discomfort that I didn’t know how to deal with. All of the things available to me to deal with it seemed self-destructive and then of course I’ve found out unfortunately through experience just how self-destructive they can be. I think there’s something beyond just the experience of abusing substances, there’s something deeper than that.

TD: It’s like a psychic pain they’re trying to remove in some way, in some form.

JB: Precisely.

TD: Well you’re doing the mental health livestream with Dr. Mike Friedman next week?

JB: Yeah. It was actually previously taped, we all got on a Zoom call. You’re talking about the one with Gerard Way, right?

TD: Of course, yeah!

JB: Oh my gosh. I was the most nervous I’ve ever been on a Zoom call.

TD: I had been going to ask if you were a fan of his growing up actually.

JB: Oh yeah! (laughs) I was like 13 years old when The Black Parade came out and it was just this perfect cosmic intersection of that record being exactly what I needed at that time. I learned it all the way through. The way that I learned how to play guitar was that I never went to guitar lessons, I just sat down and by trial and error I would try and figure out Ray Toro’s solos on The Black Parade. I started to notice patterns, like these are the number of spaces between notes you should leave. It was just hours and hours of consuming that music and I think it left a very big impression on me, not only in terms of the formal quality of my playing but a poetic impression too.

TD: So then talking to Gerard Way as if he’s a friend or a colleague, that must have been strange.

JB: I called him Gerard, like used his first name. The event was organised like a panel, so I was responding to something he had said and I was like, ‘yes, that kind of goes along with what you were saying Gerard’, and I felt so wild. I wish 13 year old Julien could’ve seen me.

TD: That’s your peak in music now. It’s all downhill from here.

JB: It is the peak! (laughs) Yes, that’s the peak.

TD: What were you talking about on the panel?

JB: It ended up being a lot about technology. I think originally the topic was open-ended, it was about how everyone was dealing with the maintenance of their mental health, during quarantine. It ended up being a lot more about social media and how we represent ourselves. Social media gives us so much editorial agency over how we appear to other people and I think that’s been stressful for me too, as a person who thinks about how I am perceived, whether I’m perceived as a good person or a bad person, whether I’m perceived as a good or bad musician. Social media’s a really tricky place which is probably why I keep it at arm’s length.

TD: Your Boygenius bandmate and friend Phoebe Bridgers, she’s very outspoken and confident on social media. Are you apprehensive about being like that online?

JB: It’s not that I’m scared to be like that. This is maybe silly but I’ve noticed this tendency in myself that when something makes me uncomfortable I just choose not to believe in it. When I was a kid, they’d say ‘if you were bad you have to move your clothes pin down from good to bad’, and I was just like ‘that’s a fucking clothes pin on a piece of paper.’ It doesn’t mean anything to me.

With social media too, I think the way I’ve isolated myself from being emotionally affected by praise or ridicule on the internet is by saying I’m going to detach myself emotionally from this and not give it enough credence. It’s very difficult for me to spend an extended amount of time on social media. I feel like sometimes I’ll just drop in and tweet something crazy and turn it off! I wish I could be more confident on it though and I envy Phoebe for it.

TD: Your first three albums, in a way, defined the first half of your 20’s. How do you foresee yourself growing as an artist and person in the second half?

JB: (pauses) I hope I stay weird. There are so many artists that are consistent and it seems like throughout their careers they distill one sort of sound and the pendulum stops swinging back and forth so much. I actually kind of hope the older I get the more emboldened I get to be weird and to do new things. That’s all you can hope for.

‘Crying Wolf’ by Julien Baker: