The first wave of punk – whether it be The Clash and Sex Pistols in the U.K. or The Ramones and The New York Dolls in the U.S. – have been rightly lauded, with much written about their successes and tribulations.

Yet the proceeding wave of punk (and emo and hardcore) that overwhelmed mainstream music in the U.S. in the 90s and 00s hasn’t been as widely discussed. Several beloved bands from those genres suddenly found themselves catapulted to intense levels of fame, in turn belying their DIY punk origins.

Why hasn’t the punk of that era been as discussed or hailed? Perhaps it’s because we often think of those types of bands from our youth – My Chemical Romance, Green Day, Blink-182, whoever – as belonging to our past; perhaps we view it as a shameful music phase which we had to pass through.

That’s what music writer Dan Ozzi has forensically examined in his excellent new book, SELLOUT: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994-2007). It offers a raucous history of punk, emo, and hardcore’s growing pains during the commerical boom of that fledgling era.

The book uses Nirvana as its foundational act, who Ozzi believes kickstarted the intense commercial interest in punk with their seminal album Nevermind: all of a sudden, major labels turned towards the underground, looking to quickly discover the next phenomenon.

Unsurprisingly, it created friction in the punk scene, which believed itself to be based on authenticity and anti-establishment values. There arose hostility towards aspiration; fans, already naturally suspicious of major labels, saw their anger only grow as their most treasured bands seemed to be taken away from them.

Ozzi looks at the examples of 11 bands who either “sold out” and found huge success and fame, or buckled under the weight of trying to make it big. There are chapters on huge artists such as Green Day, My Chemical Romance, Rise Against and, of course Blink-182; there are chapters devoted to bands who didn’t quite reach the same stratospheric heights, such as Jawbreaker, The Donnas, The Distillers, and At the Drive-In.

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

Containing original interviews and stories from those who were there, SELLOUT is an evocative picture of one of the fascinating and embittered eras of music history, when the lines between establishment and anti-establishment, realism and romanticism, became severely blurred.

We caught up with Ozzi to chat about his new book, discussing the origins of major label’s interest in punk, the humour and crassness of Blink-182, the recent pop punk revival spearheaded by the likes of Travis Barker and Machine Gun Kelly, why people at major labels aren’t always evil, and why the “sell out” era is probably over forever.

SELLOUT: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994-2007) is out now.

Tone Deaf: When did the idea for the Sellout narrative first come to you?

Dan Ozzi: I don’t know when I necessarily had the idea to turn it into a book but the time period it focuses on was just the time period I grew up in. So it was always an era I was cognizant of. Then one day I remembered that I was a writer and this period was what I knew a lot about, so I thought I should merge those two things together!

Were the bands in the book the bands you listened to yourself growing up then?

There are some that are very near and dear to my heart and then others I just like that made it into the book because they represent something important that advances the ‘sellout’ narrative of the book.

Obviously there’s been lots more literature devoted to the first wave of punk in the 70s and 80s but not so much to the second wave in the 90s and 00s. Is that just because the second wave is more recent, surely?

I think we tend to romanticise the punks of the 70s and the 80s hardcore scene because it was very new and revolutionary. I think a lot of the stuff from Green Day onwards was looked down upon by punk purists. Blink-182 are not a cool band to like according to some people!

Admittedly when I saw them as a teenager, I felt the same. I was like, “I like Dead Kennedys, this is baby stuff’. It was only in my 20s I realised their songs were catchy and that I was wrong about them. Maybe that’s why it’s been overlooked.

You’ve got to be in a certain mood to enjoy Blink’s juvenile humour.

Yeah. I was just on Rob Harvilla’s podcast and he described Blink-182 as “the least clever band in America” and I think that’s probably right (laughs). There’s no subtlety to it.

Nirvana’s Nevermind, then, was that Ground Zero for your book?

For sure because without Nirvana I don’t think a lot of this would have happened. Nirvana was adjacent to the punk scene but you wouldn’t really lump them in as a punk band. But they had this really monumental impact on independent music wherein for a decade independent music had operated completely autonomously away from the major label system. There were independent labels, promoters, fanzines.

Then eventually Nirvana came along and almost by accident became an overnight phenomenon. I talked to A&R guys who told me that after they broke things literally changed overnight. Kids didn’t want hair metal anymore, that was over (laughs). I didn’t devote a chapter to them like the other bands but they’re the focus of the introduction because it gives you this transition from the 80s into when the commercial interest in punk started.

Were there any bands you left out?

There were a couple. I’ve been doing podcast episodes where I’ve been trying to talk to people I wanted to have in the book but just didn’t have room for. Sometimes it’s heartbreaking when I’m hearing somebody talk, like Anti-Flag, who it turned out had been courted by Rick Rubin, which is astounding to me!

And then people have been like, “why didn’t you do AFI?” Obviously if I had included all the bands it would’ve been a 1,000 page book but I tried to at least cram in mentions. I mentioned that AFI went to Dreamworks, for example. Even if a band didn’t get a 40-page chapter, at least they got a mention.

You finished the book with a chapter on Against Me!. What was the reason major labels slowed down after 2007?

Against Me! were in a tough spot because when they signed that was when the music industry was grappling with declining sales and the post-file sharing new frontier that we were in. So there were a lot of tumultuous things about Against Me!’s signing.

They were maybe the only band that I mentioned in the book – and I think this happened to them twice – that their record leaked on the internet before its release. And not soon before but weeks before. That was even a new phenomenon that record labels and artists had to deal with. So Against Me! were under a lot of pressure and it didn’t help that they were also grappling with a shrinking music buying audience.

Do you think the major labels at that time had a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach? Were they thought a band like Green Day, say, were the exact same as Jawbreaker?

I think that was the case in the early days because they just didn’t understand what it was that was so appealing about punk. We have the benefit of hindsight obviously but looking back it’s like, “did you really think Jawbox were going to take off?” (laughs)

It seems so obvious now but at that time they had an approach that was all about ‘more of it’. It was about just keeping it coming and seeing if something would stick. It’s so easy for us to pick winners and losers now because we’re 20 years removed from it but at the time they were just trying anything.

Was the reaction of the wider punk community to the bands that got major label deals simply jealousy?

There were a lot of people saying fuck the major labels because it meant you were selling your art to the corporate machine, and you were working with all these shitty companies by proxy. I get that and there are valid critiques of doing business with the devil, for sure.

However, I do think a lot of it is based on just a personal slight. Like you go to see your favourite band at this place that holds 200 people and you get to go right up and touch them and maybe then afterwards you get to say hi to them. You’re their peer rather than fans.

And then the next year maybe they blow up and suddenly you don’t get to pay $8 to see them anymore, you have to pay $25 to see them, and also you don’t get to say hi to them, they’re behind a barricade now, and there’s all these new people who heard them on the radio and they don’t know the old stuff.

I just remember being younger and being annoyed at that growth. I definitely didn’t appreciate the fact that the people in these bands had bills to pay, I was just looking at it from a consumer perspective where it was annoying that I was being bombarded by these new settings and new people. While they did love to fly the ‘anti corporate’ flag, fans just felt burned on a personal level.

I think especially when punk bands have a strong sense of ethics too, you do feel a strong affinity with them.

Right. I think punk is supposed to be a very egalitarian scene where nobody is better than others, everybody is just a person making music or a person who’s a fan or whatever. Once you hear of a band getting more money and they have nicer equipment and their albums are better recorded though, it taints the balance.

Tim (McIlrath) from Rise Against has a great line in the book about that – he’s like if you didn’t screen your 7” yourself, people were like, “what the fuck”, if you’re van was too nice, they were like, “what the fuck”. Everyone was skeptical. When we’re all supposed to be equal here, why then all of a sudden is a certain band not?

It got me thinking about Warped Tour getting sponsored by Vans around 1997.

I think their first year was 1995 when it was just called Warped Tour and then the next year I think they got Vans as a sponsor and it became the Vans Warped Tour.

Obviously that’s another example of commercial and punk joining together back then.

I mean, the Warped Tour’s just been plagued by controversy from the very beginning. The controversies themselves have evolved too. At first, people thought the tour was taking away from local scenes and other touring punk bands.

Then it became a commercial endeavour where it was being criticised for having army sponsorships or pro-life organisations – for the record, I don’t think those tables should ever have had a presence there. And then there became criticisms about some of the men on the tour doing untoward things to women in the crowd! It’s just been plagued by controversy.

When I became a music journalist my attitude toward the major label people, the PRs and A&Rs, changed. You realise they’re not always soulless monsters. Did that happen to you when you were writing the book?

For sure. I have friends now who work at labels and they do that kind of work. Somebody like Jawbreaker, when I found out they went to a major label as a kid, I was annoyed. I thought it must’ve been some kind of vampire that signed them (laughs). But now I tracked the guy down and his name is Mark Kates, he was just this cool DJ from Boston.

He wasn’t a vampire, he was just a normal guy, he worked with Hole and Nirvana and Sonic Youth, and he liked Jawbreaker and just wanted to help them out! It definitely demystified the fear or hatred that I had for these kinds of people.

Did it feel like a very U.S. phenomenon when you were researching the book or was it the same everywhere?

I really kept it within the U.S.. I don’t really know if this existed in the U.K. or not. I think the U.K. tends to treat its rock stars and celebrities a bit differently than America does. I think it’s very cheeky and they try to cut artists down to size if their heads are getting too big. In America we just murder them – I mean, they sent us John Lennon and we killed him! We’re very serious about grievances that we have with rising celebrities.

I think in the U.K. there’s more of a class divide in punk. There was the recent example of Sleaford Mods and IDLES bickering last year because Sleaford Mods said that they were essentially middle class posers.

That’s one thing that really got overshadowed with all the sellout accusations that Green Day got. It doesn’t get talked about a lot but Green Day are from Rodeo, which is this really shitty town outside the Bay Area that’s just basically refineries and then some homes. If somebody waves $200,000 at them, are they not supposed to take that? The socio-economic aspects of it really didn’t get talked about a lot at that time.

Do you think some of the bands in the book reached a level of fame that was too much? I’m thinking of Green Day with the American Idiot musical, for example.

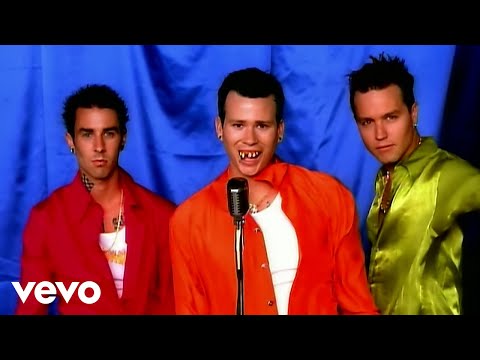

Who’s to say where the limit on fame should be! I was just talking about the music video for Blink-182’s ‘All the Small Things’, where they were parodying boy bands like NSYNC and Backstreet Boys.

I think they were also nodding to the fact they were also a boy band now. They were as big as the pop starlets on MTV. So Blink-182 tried to ride this line like, ‘we’re just some little kids from California, making our pop punk songs’ but also selling as many records as someone like Beyoncé does!

How far removed from that selling out period do you think we are now?

I think it’s definitely over. I think money is so much harder to make in the music industry. You don’t hear too much about big cheques getting written anymore. Major labels used to just write shit off. “Oh, this band didn’t work out? Oh well, that’s a tax write off, maybe next time.”

Now, if you get the rare opportunity where a label gives you money, they want something back for that. Maybe they’re doing a 360 deal where they get a cut of your merch. Nobody’s just handing out cheques willy nilly anymore which seemed like it happened a lot more frequently in the 90s.

This recent pop punk revival with Travis Barker working with the likes of Willow Smith and Machine Gun Kelly, do you think that could bring back a revival in punk in the major labels

Maybe but it just seems so nostalgic, you know? It just seems like Machine Gun Kelly is popular because he started making these pop punk songs under the tutelage of Travis Barker, who’s been around for 30 years. It’s hard to look at it as a fresh thing because he almost seems like a puppet and Travis Barker is pulling his strings.

And you look at these shitty emo nights that are popular, it’s nostalgic too. It’s like, “hey, remember that fad you had in high school where you were a fucking little loser baby, well why don’t you come to this place and we’ll celebrate how we were all little loser babies!” I just despise the angle in which it’s being presented now as this sort of throwback thing.

How do you think the streaming era changed the approach of major labels to the punk scene?

I think they were less prone to taking chances. They used to look at a band and give them $300,000 and do a push in the fall of 2001, or whatever.

But now it feels like A&R is much more data-driven where they’re less interested in a band’s artistic worth and they’re more interested in how many streams they get or how many followers on TikTok they have. So they just crunch the numbers and see how much they should give them and how much they would make off of that. But it does seem that gut instinct and intuition of the traditional A&R role has gone by the wayside.