Britain has always loved a working class musical hero. Tony Blair certainly knew it when he capitalised on the swaggering success of the Gallagher brothers, weaponising the power of Oasis in the rise of New Labour.

By the turn-of-the-century, however, britpop had divulged too much in the glamorisation of the ‘rock ‘n’ roll’ lifestyle; it no longer felt relevant or relatable in the existential first few years of the 21st century.

An increasingly dominant force in music was U.S. hip hop, but for a kid from the middle of England, it wasn’t exactly relatable either: Eminem may have been the biggest rapper in the world, and while thousands across the Atlantic indulged in his verses, it was difficult to really understand the Detroit world that he discussed.

When it comes down to it, we all want to see ourselves reflected back in the music we listen to, and for adolescent Britain in 2002, Mike Skinner was the person who provided this.

As leader of The Streets, Skinner dropped Original Pirate Material that year and made the seminal soundtrack for an entire generation. Performing street poetics in a ruggedly regional accent, Skinner spun genuinely moving tales of working class Britain, never demeaning and always genuine.

And it came from a deeply personal place: as Skinner himself said, he was “Barratt class: suburban estates, not poor but not much money about, really boring.”

Love Music?

Get your daily dose of metal, rock, indie, pop, and everything else in between.

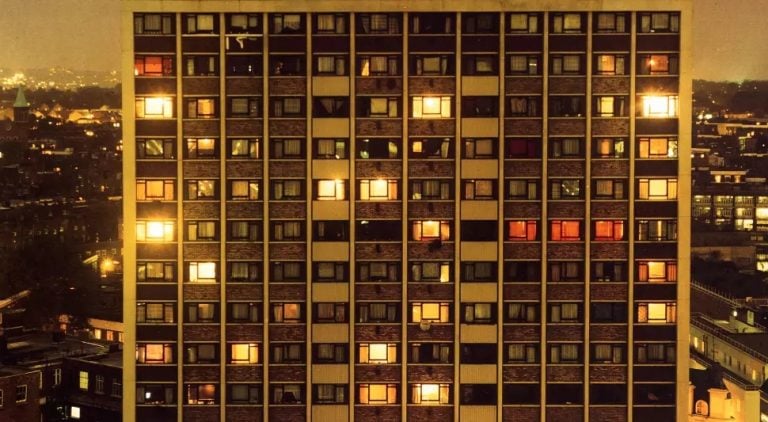

Original Pirate Material revels in its ordinariness, turning the banal experience of grey-skied British towns and cities into subtle art. Sometimes you suffered heartbreak, sometimes you were hungover, sometimes life was just a dull waste of time (it feels relevant that Skinner decided to soundtrack the first Inbetweeners film, itself a cultural artefact of a particularly dreary British suburban way of life).

Born in the industrial smog of Birmingham, by the time of recording The Streets’ debut album, Skinner was holed up in a small room in South London. It was in this nondescript place that the bulk of the album was made, a proper bedroom DIY effort, using just simple casio keyboards, loop machines, and a makeshift vocal booth.

Skinner might have been influenced by U.S. hip hop icons like Nas and Wu-Tang Clan, but he didn’t make the mistake of other burgeoning U.K. rappers and try to be them; his style was no meagre ripoff of those predecessors, but a regional variation on it (as he sings in the third track ‘Let’s Push Things Forward’, “Around here we say birds, not bitches”).

That’s why the true genius of Original Pirate Material was in merging his lyrical content with the increasingly popular U.K. garage sound. The 2-step beats encapsulated British urban music, but unlike the often frenetic club garage at that time, Skinner’s version was earnest and soft, often surprisingly meditative.

He also effortlessly hopped between genres throughout the album, experimenting with dub, house, and reggae (like Andrew Weatherall, he was first and foremost an avid music fan).

The test of an original work is in its influence on proceeding generations, and Original Pirate Material‘s touch is still felt in current British music: it’s in the political shouting of Sleaford Mods and IDLES; it’s in the massive cultural domination of grime and drill; it’s in the cheeky chappy style of singer-songwriters like Sam Fender.

There aren’t many unassuming artists who can genuinely claim to captured a specific time and place in their music, but Skinner achieved exactly that. Finding pathos in the dark and dreary adolescence of a Britain unsure of itself, 20 years on Original Pirate Material remains a masterpiece.